Officials Who Kidnapped Hotel Rwanda Hero Are Not Immune from Suit

April 3, 2023

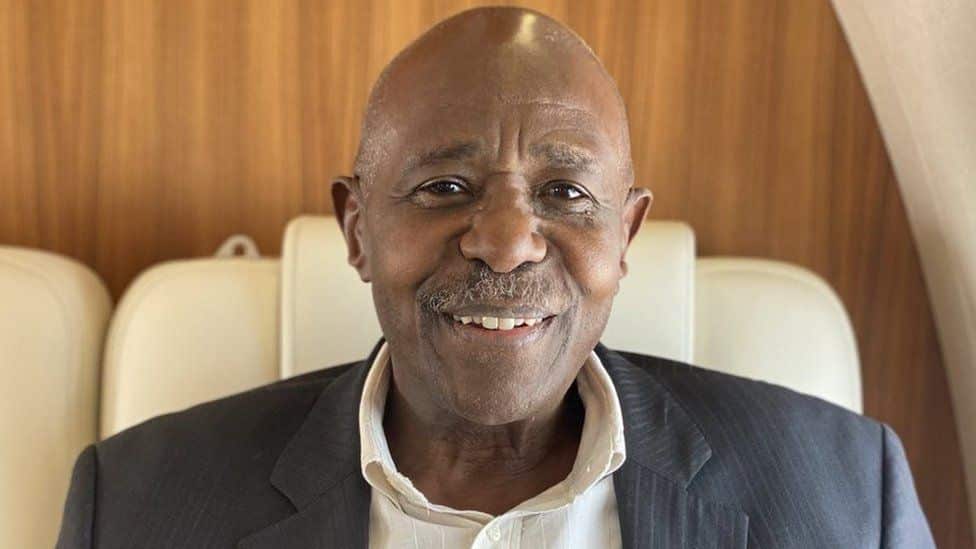

In 1994, Paul Rusesabagina was the manager of a hotel in Kigali, Rwanda. During the genocide, he sheltered 1,268 Hutu and Tutsi refugees, all of whom survived. His courage inspired the film “Hotel Rwanda,” and in 2005 President Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Rusesabagina became a human rights advocate and vocal critic of Rwandan president Paul Kagame. He also became a permanent resident of the United States.

Rwandan officials allegedly began to surveil Rusesabagina in the United States with spyware on his phone. In 2020, they fraudulently induced him to travel to Burundi to speak to church groups about the genocide and kidnapped him by diverting his chartered plane to Rwanda where he was imprisoned, tried, and sentenced to 25 years in jail. Rusesabagina’s wife and six children sued Rwanda, Kagame, and three Rwandan officials who planned the kidnapping in federal District Court for the District of Columbia, alleging misrepresentation, false imprisonment, and violations of the federal Electronic Communications Privacy Act and Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA), among other claims. (Disclosure: I filed a declaration on the customary international law of foreign official immunity in support of the plaintiffs.)

On March 16, 2023, the district court (Judge Richard Leon) held that some of the plaintiffs’ claims could go forward against the three Rwandan officials. A week later, after negotiations with the White House, Rwanda commuted Rusesabagina’s sentence. On March 29, he returned home to the United States. Having succeeded in gaining Rusesabagina’s freedom, the plaintiffs moved on March 31 to dismiss their complaint with prejudice.

In this post, I describe Judge Leon’s decisions, which navigated expertly through a minefield of objections raised by the defendants, including foreign sovereign immunity, head of state immunity, personal jurisdiction, service of process, and the act of state doctrine. The Rusesabagina case is significant because it shows that human rights litigation can sometimes support, rather than interfere with, the diplomatic efforts of the United States.

The FSIA and Head-of-State Immunity

In his earlier opinion, Judge Leon dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims against Rwanda under the FSIA and their claims against President Kagame based on head-of-state immunity.

As a foreign state, Rwanda is immune from suit in U.S. courts under the FSIA unless an exception to immunity applies. Plaintiffs relied on the FSIA’s commercial activity exception, arguing that Rwanda’s efforts to recruit Rusesabagina to speak at churches in Burundi was a commercial activity. But the court held that this activity was not the “gravamen” of their complaint. Plaintiffs also argued that their claims fell within the FSIA’s noncommercial tort exception. But the court held that their fraud claim fell within an exception to the exception and the other claims were excluded because the alleged torts did not occur entirely within the United States.

The court dismissed the claims against President Kagame because, as a sitting head of state, he is entitled to absolute immunity in U.S. courts. The court rejected plaintiffs’ arguments that Kagame was not entitled to immunity unless the State Department filed a suggestion of immunity and that the court should disregard his immunity because of the heinous nature of the allegations.

Foreign Official Immunity

In his March 16 opinion, Judge Leon addressed objections raised by the three remaining defendants: the Secretary General of the Rwandan National Intelligence and Security Services (RNISS), an official who oversees the Rwandan Intelligence Bureau (RIB), and Rwanda’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.

Under international law, foreign officials are entitled to various forms of foreign official immunity. (For an overview of the law on foreign official immunity in the United States, see here.) In the United States the immunities of foreign diplomats and consular officials are governed by two treaties—the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (VCDR) and the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), respectively—whereas the immunity of other foreign officials is governed by federal common law. As the district court explained, U.S. courts recognize two forms of foreign official immunity: status-based immunity and conduct-based immunity. Judge Leon correctly held that these officials were entitled to neither.

Status-based immunity, the court noted, “is reserved for diplomats and heads of state and attaches ‘regardless of the substance of the claim’” (quoting Lewis v. Mutond (D.C. Cir. 2019)). The two officials from the RNISS and RIB are not heads of state, heads of government or foreign ministers, the only three officials to which head of state immunity attaches. Nor are they Rwandan diplomats.

The third official, Rwanda’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom is a diplomat, but he is not entitled to diplomatic immunity in this case, the court held, because he is not accredited to the United States. Under the VCDR, diplomatic agents are entitled to immunity from the criminal and civil jurisdiction “of the receiving state.” “By its express terms,” Judge Leon noted, “Article 31 protects only those diplomats who have been received by the state that might exercise jurisdiction.” Third states are bound under Article 40 to extend immunity only in limited circumstances.

In contrast to status-based immunity, conduct-based immunity shields foreign officials from suits based on acts taken in their official capacities. By agreement of the parties, the district court in this case applied the three-part test set forth in Restatement (Second) of Foreign Relations Law § 66(f), which asks: (1) whether the defendant is a public minister, official, or agent of the foreign state; (2) whether the acts underlying the suit were performed in their official capacity; and (3) whether the effect of exercising jurisdiction would be to enforce a rule of law against the state. The D.C. Circuit held in Lewis v. Mutond that the third requirement is met only if the defendants are sued in their official capacities and any judgment would be enforceable against the state. Because here the defendants were sued in their personal capacities and a judgment would not be enforceable against Rwanda, Judge Leon correctly held that the third requirement was not met.

Although the district court did not address the issue, it appears to me that the second requirement—that the acts underlying the suit were performed in the defendants’ official capacities—was also not met here. As I explained in my declaration in support of the plaintiffs, international law does not recognize conduct-based immunity for serious human rights violations. And as Chimène Keitner and I have argued, federal courts should not, in the process of developing federal common law, extend more immunity to foreign officials than international law requires. Surveilling, kidnapping, imprisoning, and torturing Rusesabagina cannot be considered acts taken in an official capacity for purposes of conduct-based immunity.

Personal Jurisdiction

The defendants also moved to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(k). Rule 4(k)(1)(a) allows a federal court to establish personal jurisdiction over a defendant if the defendant would be subject to personal jurisdiction in state court. The District of Columbia’s long-arm statute authorizes personal jurisdiction to the extent permitted by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. But because the plaintiffs’ claims did not arise out of or relate to any contacts with DC, the court correctly held that Rule 4(k)(1) did not establish personal jurisdiction.

Rule 4(k)(2) allows a federal court to establish personal jurisdiction for claims arising under federal law if the defendant is not subject to personal jurisdiction in any state and the exercise of personal jurisdiction is consistent with the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. In this case, plaintiffs brought claims under the federal Electronic Communications Privacy Act and the Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA), and the foreign officials failed to identify any other state in which they would be subject to personal jurisdiction.

The critical question was whether the exercise of jurisdiction would be consistent with due process. As Judge Leon noted, for personal jurisdiction under Rule 4(k)(2), a court must evaluate not just the defendants’ contacts with the forum state (DC) but with the United States as a whole. The court correctly held that the defendants’ conduct—attributable to all the co-conspirators—of illegally monitoring Rusesabagina’s phone in the United States and fraudulently inducing him to leave the United States on a trip he thought would take him to Burundi was sufficient to establish minimum contacts with the United States.

Judge Leon further held that the exercise of personal jurisdiction would be reasonable. Although the burden on the defendants of defending themselves in U.S. court would be “significant,” the court concluded that it was outweighed by the interests of the United States in adjudicating the case, the interests of the plaintiffs in effective relief, and the interests of the judicial system in efficient resolution of the claims. The court noted that two of the plaintiffs are U.S. citizens and that four others, including Rusesabagina, are U.S. permanent residents. Moreover, the complaint alleges “criminal conduct directed at the United States for the purposes of kidnapping and mistreating a resident of the United States.”

Having established personal jurisdiction under Rule 4(k)(2) with respect to the plaintiffs’ federal claims, the court held that it had pendent jurisdiction over the plaintiffs’ state law claims.

Service of Process

A court may not exercise personal jurisdiction over a defendant unless the defendant has been properly served with process. The three officials were each served with process by mail, one in the United Kingdom and two in Rwanda. The United Kingdom is party to the Hague Service Convention, whereas Rwanda is not.

Rule 4(f)(1) authorizes service “by any internationally agreed means of service that is reasonably calculated to give notice, such as those authorized by the Hague [Service] Convention.” Article 10(a) of the Convention authorizes service by postal channels, unless the receiving country objects, which the United Kingdom has not. Rwanda’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom was served by international priority mail at his London office.

If there is no internationally agreed means of service, as is true for defendants in Rwanda, Rule 4(f)(2)(C)(ii)authorizes service by “any form of mail that the clerk addresses and sends to the individual and that requires a signed receipt” unless prohibited by the foreign country’s law. The other two defendants were served in this manner at their offices in Rwanda, and plaintiffs provided two affidavits from experts on Rwandan law that service by mail is not prohibited. Therefore, the court concluded that all the defendants were properly served.

Act of State Doctrine

The district court went on to hold that some but not all of the plaintiff’s claims were barred by the act of state doctrine. Quoting the Supreme Court’s decision in W.S. Kirkpatrick & Co. v. Environmental Tectonics Corp., International (1990), the court noted that “[t]he act of state doctrine prohibits U.S. courts from ‘declar[ing] invalid the official act of a foreign sovereign performed within its own territory.’”

Because the doctrine is limited to official acts performed within a foreign sovereign’s own territory, the court correctly held that the doctrine did not bar plaintiffs’ claims based on acts that occurred outside Rwanda, including surveilling Rusesabagina, making false statements to lure him from his home in Texas, and diverting his plane from Burundi to Rwanda.

But the court held that the act of state doctrine did bar plaintiffs’ claims based on acts the occurred inside Rwanda, specifically the common-law claims that “contest the legality of Rwanda’s imprisonment of Rusesabagina and his treatment by his Rwandan captors.” The court reasoned that these claims “cannot be resolved in plaintiffs’ favor without a finding that official acts taken by Rwanda in its own territory were unlawful.” The court made an exception only for the plaintiffs’ torture claim under the TVPA, concluding that “enactment of the TVPA represents a clear statement by Congress that federal courts should not cite the act of state doctrine as grounds to refuse to hear a case to which the statute applies.”

In my view, the district court erred in finding that the act of state doctrine barred the plaintiffs’ common law claims. These claims did not challenge the validity of the Rusesabagina’s detention and treatment in Rwanda; they challenged its legality. Validity and legality are different questions. Thus, as the Second Circuit recently held, the act of state doctrine does not bar antitrust claims for price fixing even if the price fixing was implemented through presidential decrees of a foreign government. The validity of the decrees was “separate from the question” of price fixing. “We may give the Presidential Order and Circulars their full purported legal effect,” the Second Circuit reasoned, “and still conclude that Plaintiffs have plausibly alleged illegal price-fixing under the Sherman Act.”

The same is true in this case. Plaintiffs’ claims for solatium, false imprisonment, assault, battery, and loss of consortium would not require the court to find that Rwanda’s acts within its own territory were “invalid.” And that is all that the act of state doctrine prohibits.

Conclusion

According to news reports, the United States had been negotiating with Rwanda for months, attempting to secure Rusesabagina’s release. It is telling that the negotiations succeeded just a week after Judge Leon decided that the case could go forward.

It has become a consistent refrain that transnational litigation may cause “international discord” and that courts should proceed with “caution,” particularly in human rights cases against foreign officials. In my view, these concerns are often overblown and sometimes non-existent. But the Rusesabagina case shows that human rights litigation can sometimes support rather than hinder U.S. diplomacy. We may never know precisely what finally convinced Rwanda to free Paul Rusesabagina. But the prospect of continuing litigation in U.S. courts and the possibility of ending that litigation must surely have influenced the Rwandan government.