What Does the State Department Think About the Transit Pipelines Treaty?

February 15, 2024

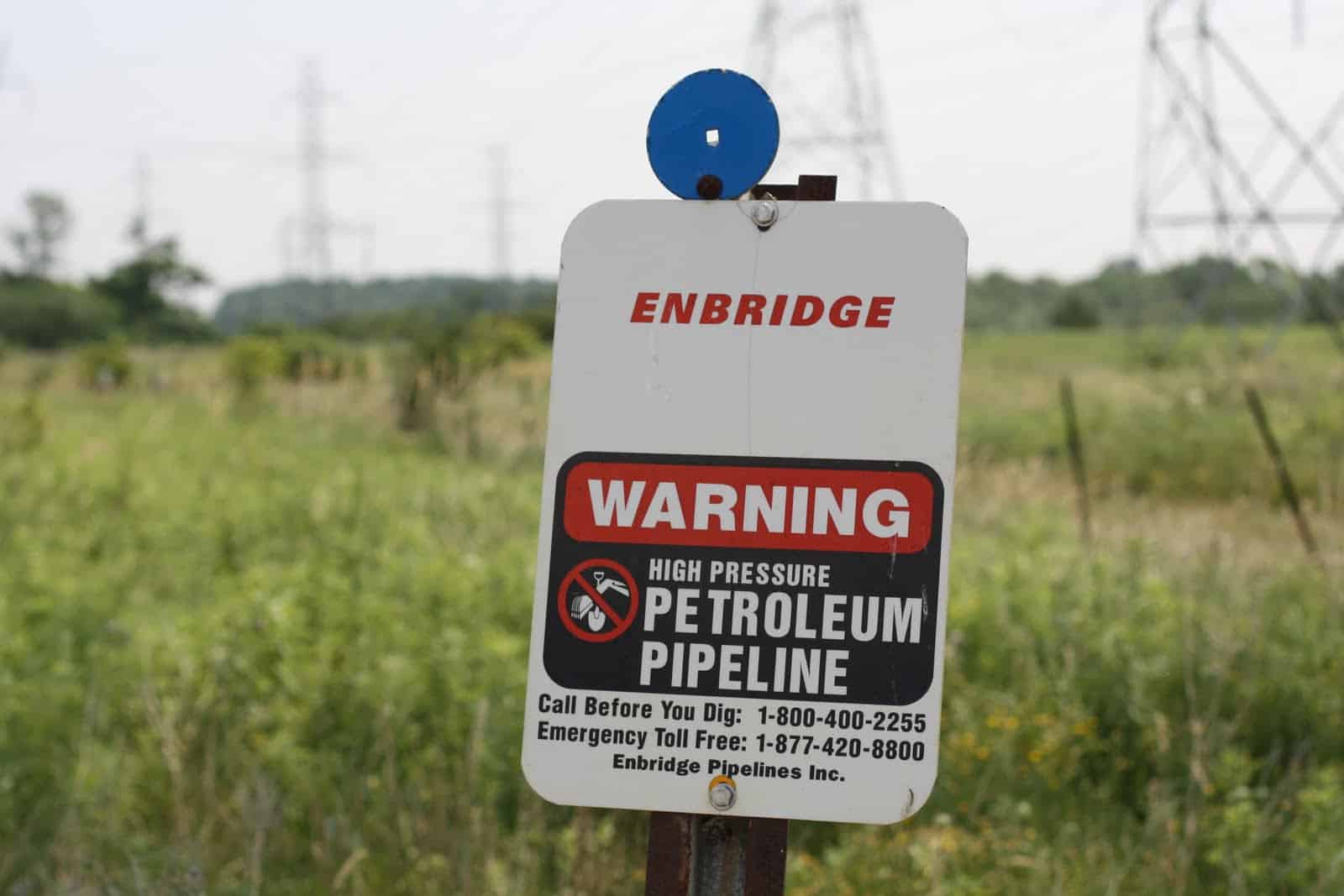

On February 8, 2024, the Seventh Circuit heard argument in Bad River Band v. Enbridge Energy Co. Enbridge, a Canadian company, owns and operates a pipeline that transports light crude oil and natural gas liquids from Canadian oil fields to the United States and Ontario. The Bad River Band of Chippewa Indians sued Enbridge for trespass, after its easements through various Reservation parcels expired, fearing that the 70-year-old pipeline would rupture and cause an environmental disaster. The District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin (Judge William M. Conley) found that the pipeline trespasses on the Bad River Reservation and ordered it shut down by June 16, 2026.

On appeal, Enbridge argues that Judge Conley’s order violates the Transit Pipelines Treaty between Canada and the United States. (There is also an 1854 treaty between the Chippewa and the United States that bears on the case, which I will not address here.) The pipeline treaty is also at issue in litigation between Enbridge and the State of Michigan, in which Michigan seeks to enjoin operation of the pipeline across the Straits of Mackinac (between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) because of similar environmental concerns.

In response to Michigan’s action, Canada initiated the dispute resolution process with the United States under Article IX of the pipeline treaty. Canada also filed an amicus brief in support of Enbridge’s appeal to the Seventh Circuit in the Bad River Band case. Canada argues that Judge Conley’s order violates Article II of the treaty, which says that “[n]o public authority … shall institute any measures” that “would have the effect of, impeding, diverting, redirecting or interfering with in any way the transmission of hydrocarbon in transit.” Naturally wishing to know how the State Department interprets the treaty, the Seventh Circuit asked the United States to file its own amicus brief. So far, the State Department has remained silent.

The Transit Pipelines Treaty

Canada and the United States concluded the Transit Pipelines Treaty in 1977. Article II(1) of the treaty provides:

No public authority in the territory of either Party shall institute any measures, other than those provided for in Article V, which are intended to, or which would have the effect of, impeding, diverting, redirecting or interfering with in any way the transmission of hydrocarbon in transit.

Article V, to which this provision refers, provides that the flow of hydrocarbons “may be temporarily reduced or stopped” in case of a “natural disaster, an operating emergency, or other demonstrable need” “with the approval of the appropriate regulatory authorities of the Party in whose territory such disaster, emergency or other demonstrable need occurs.” Canada argues that Article V’s exception does not permit Judge Conley’s order because (1) a trespass is not a natural disaster etc.; (2) the shutdown is permanent, not temporary; and (3) his order was not approved by the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), which Canada says is the appropriate regulatory authority in the United States.

But Article V is not the only exception to Article II. Article IV of the treaty further provides:

1. Notwithstanding the provisions of Article II and paragraph 2 of Article III, a Transit Pipeline and the transmission of hydrocarbons through a Transit Pipeline shall be subject to regulations by the appropriate governmental authorities having jurisdiction over such Transit Pipeline in the same manner as for any other pipelines or the transmission of hydrocarbons by pipeline subject to the authority of such governmental authorities with respect to such matters as the following:

a. pipeline safety and technical pipeline construction and operation standards;

b. environmental protection;

c. rates, tolls, tariffs and financial regulations relating to pipelines;

d. reporting requirements, statistical and financial information concerning pipeline operations and information concerning valuation of pipeline properties.

2. All regulations, requirements, terms and conditions imposed under paragraph 1 shall be just and reasonable, and shall always, under substantially similar circumstances with respect to all hydrocarbons transmitted in similar pipelines, other than intra-provincial and intra-state pipelines, be applied equally to all persons and in the same manner.

Article IV makes clear that pipelines covered by the treaty remain subject to regulations in Canada and the United States so long as they are reasonable and are applied without discrimination.

Canada notes that Article IV does not expressly permit the flow of hydrocarbons to be “reduced or stopped” as Article V does. But Article V focuses narrowly on situations of emergency and natural disaster in which temporary shutdowns might be necessary. Article IV applies to regulation more broadly, and it would have made no sense to identify specific remedies like shutdowns in such a provision. The power to regulate necessarily includes the power to prohibit. And property rights, absent an easement, always carry the right to exclude.

Canada also argues that only the PHMSA, and not a federal district court, is an “appropriate governmental authorit[y] having jurisdiction” over the pipeline under Article IV. But this phrase in Article IV is different—and broader—than the corresponding phrase in Article V, “appropriate regulatory authorities,” which Canada says applies exclusively to the PHMSA. Under a plain-language reading, a federal district court certainly qualifies as a “governmental authority,” just as Canada argues that it qualifies as a “public authority” under Article II.

Finally, Canada objects that there is no express “trespass/property rights exception” in the treaty. But it is not clear why there needs to be one. Article IV refers broadly to “[a]ll regulations, requirements, terms and conditions.” Paragraph 1 identifies four specific kinds of regulation, but the introductory phrase “such matters as the following” clearly indicates that the list is not exclusive. And one of these matters is environmental protection, which is the reason the Bad River Band decided not to renew Enbridge’s easement across its Reservation and the reason Michigan seeks to revoke its easement across the Mackinac Straits.

The absence of an express trespass exception, Canada argues, “reflects the Treaty Parties’ stated intent to pursue an international public policy favoring trans-border cooperation and energy security, notwithstanding policies that might be pursued by local ‘public authorities’ and notwithstanding private property rights, which can be vindicated by means of financial compensation while keeping important international pipelines in operation.” Canada reads the treaty, in other words, to have overridden all private property rights under state, provincial, and tribal law, except claims for monetary compensation, despite saying not one word to that effect.

The Canada-U.S. Dispute Resolution Process

Apart from the treaty’s substantive provisions, Canada also argues that the dispute resolution process it has initiated under the treaty effectively preempts the district court’s jurisdiction. “[O]nce a colorable Treaty objection is raised by a Party to the 1977 Treaty who invokes the Article IX process,” Canada says, “domestic courts should defer to the Article IX process to ultimately resolve the dispute, thereby giving effect to Article IX and avoiding undue judicial interference in the conduct of international relations.”

Article IX provides that “[a]ny dispute between the Parties regarding the interpretation, application or operation of this Agreement shall, so far as possible, be settled by negotiation between them.” It goes on to state that any “dispute which is not settled by negotiation shall be submitted to arbitration at the request of either Party.” It appears that when Canada filed its amicus brief in September, it was still in the negotiation phase of this process with the United States.

It is certainly possible for a treaty to preempt domestic court proceedings. The Algiers Accords that ended the Iran hostage crisis, for example, expressly stated:

[T]he United States agrees to terminate all legal proceedings in United States courts involving claims of United States persons and institutions against Iran and its state enterprises, to nullify all attachments and judgments obtained therein, to prohibit all further litigation based on such claims, and to bring about the termination of such claims through binding arbitration.

Article IX, however, says nothing about preempting litigation in domestic courts. In the absence of such an express statement, the normal rule is for domestic court proceedings to continue as usual. If those proceedings result in violations of the treaty, Article IX provides recourse. But there is nothing in this treaty that even remotely suggests that domestic courts must suspend their proceedings in the interim.

What Does the State Department Think?

Canada has clearly expressed its interpretation of the treaty to the Seventh Circuit, but the United States, so far, has not. Certainly, the United States has a position on the treaty’s interpretation. According to Canada, there have already been two negotiating sessions, and the State Department does not go into such sessions without a view of what a treaty means.

The treaty’s interpretation is at issue in two separate cases proceeding in two separate circuits. There is a distinct possibility that the courts in these circuits will disagree over the treaty’s proper interpretation. The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that, “[a]lthough not conclusive, the meaning attributed to treaty provisions by the Government agencies charged with their negotiation and enforcement is entitled to great weight.” I strongly suspect that in these cases, whatever the State Department says will carry the day.

It is sometimes said that that the United States should speak with “one voice” in foreign affairs. But it is difficult to know what U.S. courts should say to Canada when the most important voice remains silent. At oral argument, Judge Easterbrook called the United States’ silence “extraordinary” (minute 16:05). It is hard to disagree.