Deciding the “Real Party in Interest” in FSIA Litigation

April 2, 2025

The Second Circuit has categorized a recent case against an individual Egyptian official as a case against the Egyptian government as the “real party in interest.” The case, Hussein v. Maait, was then dismissed because Egypt was immune from suit. The court of appeals did a nice job laying out and applying the relevant “real party in interest” analysis, although it could have better connected its analysis to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) and better articulated the significance of international practice.

Background

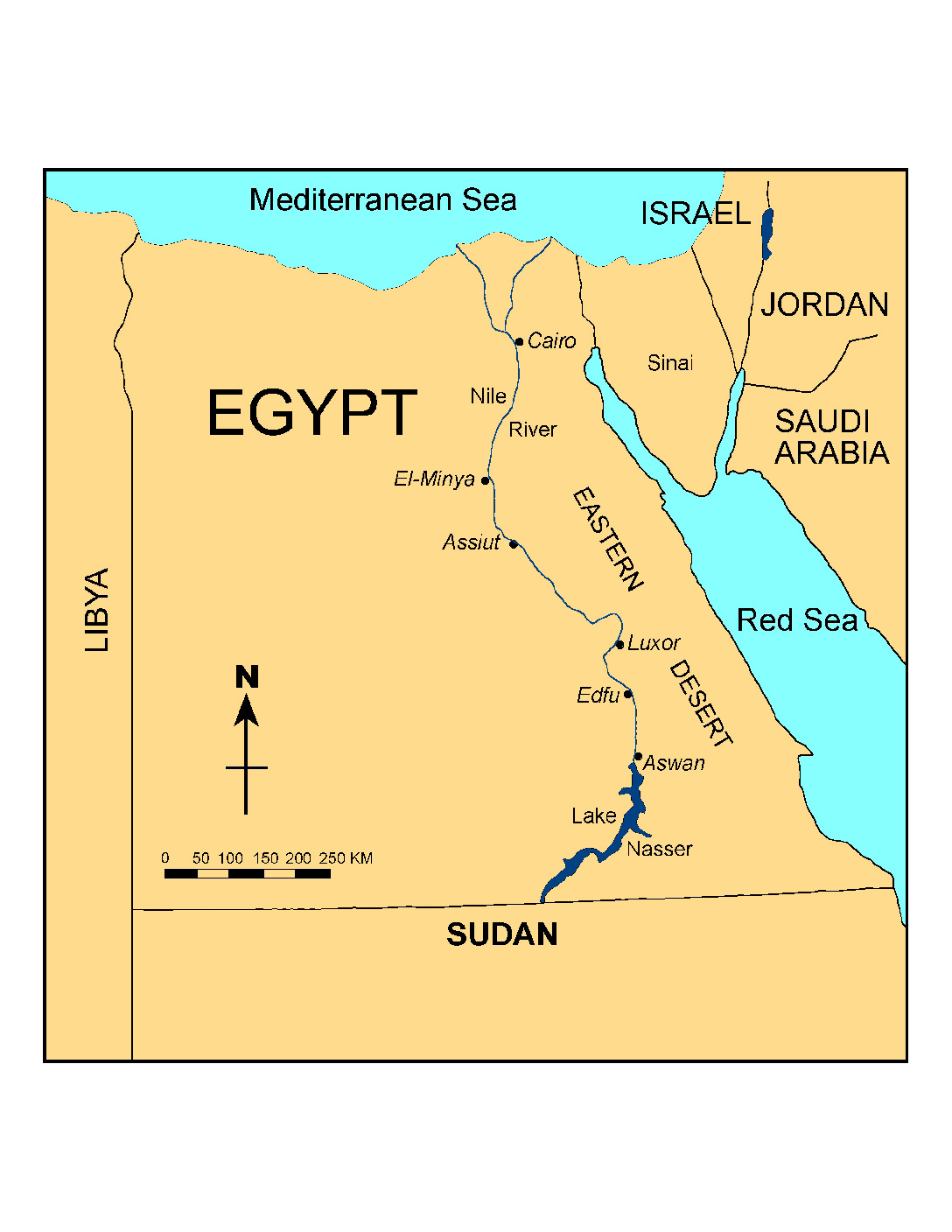

Dr. Ahmed Diaa Eldin Hussein allegedly had a $15.7 million equity interest in SIMO Middle East Paper (“SIMO”) that was expropriated by the Egyptian government in 1999. Various parties sought to reverse the government’s action, resulting in an administrative court ruling in Egypt and a government decree, which together purportedly require that Hussein’s interest in SIMO be returned to him. Hussein allegedly communicated repeatedly and unsuccessfully with Egypt’s Minister of Finance, Dr. Mohamed Ahmet Maait, to secure compensation.

In December 2021, Hussein sued in New York state court to enforce the Egyptian ruling and decree. The suit was brought against Maait “in his official capacity as Minister of Finance of the Arab Republic of Egypt.” Service was effectuated on the Arab Republic of Egypt, following the FSIA’s requirements for serving a foreign sovereign. The service package included an FSIA Notice of Suit and Attachment that stated “the above named defendant can be defined under 28 U.S.C. § 1603(b) as an agency of the foreign state of Egypt”.

Maait filed a notice for removal in the Southern District of New York, citing 28 U.S.C. § 1441(d), which allows for removal of any civil action against a foreign state as defined in 1603(a) of the FSIA. Maait argued that Egypt was the real party in interest in this suit, not Maait himself, and that the FSIA accordingly applied. Maait had missed the generally-applicable 30 day statutory deadline for removal under 28 U.S.C. § 1446(b), but that deadline may be enlarged for removal by foreign sovereigns.

Once in federal court before Judge Rakoff, Maait moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction, again arguing that the real party interest was not him but instead the government of Egypt, which can only be sued pursuant to the FSIA. In Samantar v. Yousuf (2010), the Supreme Court had held that FSIA does not ordinarily extend to individual officers of foreign sovereign, such as Maait, even when they are sued for conduct taken in their official capacity. But the Court did note in Samantar that some actions nominally against a foreign official could implicate the foreign sovereign itself, so that the foreign state “is the real party in interest” in the suit and the FSIA applies.

Maait relied on Samantar to argue that although he was the defendant, Egypt was the real party in interest, so that the FSIA governs the suit, and that none of the exceptions to FSIA immunity applies, so that dismissal was required. Hussein argued that his failure to receive funds under the Egyptian judgment was a personal wrong by Maait, making Maait personally liable to Hussein; he also argued that if Egypt was the real party in interest, the FSIA’s commercial activity exception applied. The district court dismissed, holding that Egypt was the real party in interest and that the commercial activity exception to immunity did not apply.

The “Real Party in Interest”

On appeal, Hussein renewed his argument that the district court should have remanded the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction because the suit was brought against an official of a foreign state, not against Egypt, and thus could not be removed under the special rules for foreign sovereigns. Maait argued again that under the Samantar framework, the Government of Egypt is the real party in interest, so Hussien’s suit is governed by the FSIA and should be dismissed, not remanded.

The case is important for what it says about the “real party in interest” inquiry under the FSIA. The Second Circuit, noting that the Supreme Court provided little guidance on this question, adopted three non-exclusive factors to guide the inquiry. First, drawing from language in Samantar, courts should consider “the process by which the plaintiff sues the defendant, looking to whether the plaintiff states that he is suing the foreign official in his personal capacity or in his official capacity.” Second, courts should look to the substance of the liability claim. Even if a plaintiff insists that the defendant is sued in a personal capacity, the court has an obligation to evaluate the substance of the suit to determine whether it is actually directed at the government. Third, courts are to consider the relief that the plaintiff seeks and the party targeted to provide that relief.

Applying those three factors to Hussein’s case, the court of appeals noted first that Hussien explicitly sued Maait in his official capacity and that he sought service of process under the FSIA. More broadly, before suit was initiated in New York, Hussein had sought relief from various Egyptian government officials and had sought arbitration with the government of Egypt to resolve the dispute.

Second, the substance of Hussien’s suit, according to the court of appeals, also points toward Egypt as the real party in interest because Hussien seeks enforcement of two government actions – an administrative court judgment and an executive decree. The executive decree does not name Maait but instead directs the “Minister of Finance” to take action. Third, if the plaintiff prevails, the claims would be satisfied by the Egyptian government, not by Maait himself. All three relevant factors point to Egypt as the real party in interest.

Hussein also argued that Maait acted ultra vires when he failed to issue Hussein’s compensation and that he could not therefore be acting on behalf of the government, so that the suit is against Maait as an individual, not as part of the government. How, in other words, can the suit be against the government, if it alleges that Maait did not act as the government directed him to do? The Second Circuit focused on the language of the government decree, reasoning that it was open ended (“provide all necessary financial credits”) and did not specify either an amount of money or Hussien as a recipient, making it unclear whether Maait failed to follow it. Even if Maait did fail to faithfully execute the decree, the court reasoned that such failure should be understood as a decision by the Egyptian government not to allocate funds for this purpose, and not that Maait acted outside of his power. Finally, Maait ultimately seeks compensation from the federal treasury through the enforcement of a judgment, and there is no allegation that Maait took money that should belong to Hussien.

The Second Circuit’s ultra vires analysis correctly distinguished two lines of cases, but it did so in ways that point to weaknesses in its generally strong analysis. First, the court distinguished cases against the U.S. government holding that the real party in interest is the individual who is acting ultra vires – so long as the suit is for injunctive relief. The court was correct to distinguish that line of cases because the claimant in this case seeks monetary relief. But the court failed to note that the relevant law in this case is the FSIA, full stop. Cases against the U.S. government involve different statutes and different considerations and should be applied very cautiously in the FSIA context.

Second, the court dedicated a footnote to distinguishing cases against individual foreign officials holding that they lack common law immunity for claims that they committed torture. Here, too, the court was correct to distinguish those cases, both because they involve torture and because they do not involve interpretation of the FSIA. But international practice might well be an important consideration when interpreting the FSIA in this context. That is, if international practice generally treats a suit against a government official as a suit against the government itself for immunity purposes, courts should consider that practice when interpreting the FSIA to determine whether a suit against an individual official is one in which the state is the real party in interest. The statute was enacted with international law in mind, and courts should be cautious in denying an immunity that international law or practice would require.

Conclusion

The “real party in interest” question is an important part of FSIA litigation. But it is worth noting that even if the government of Egypt were not the “real party in interest,” Maait may himself have been entitled to common law immunity if he were acting in an official capacity. In this case, Maait appears to have been acting within the scope of his authority to make decisions on behalf of the Egyptian government, which may entitle him to common law immunity. The case may accordingly have been dismissed on immunity grounds in either event – but the generous time for removal applies only to foreign states under the FSIA, not to individual officials. So, the common law immunity issue would have been the state court’s decision to make.