Constitutional Issues in the Sudan Claims Resolution Act

September 20, 2023

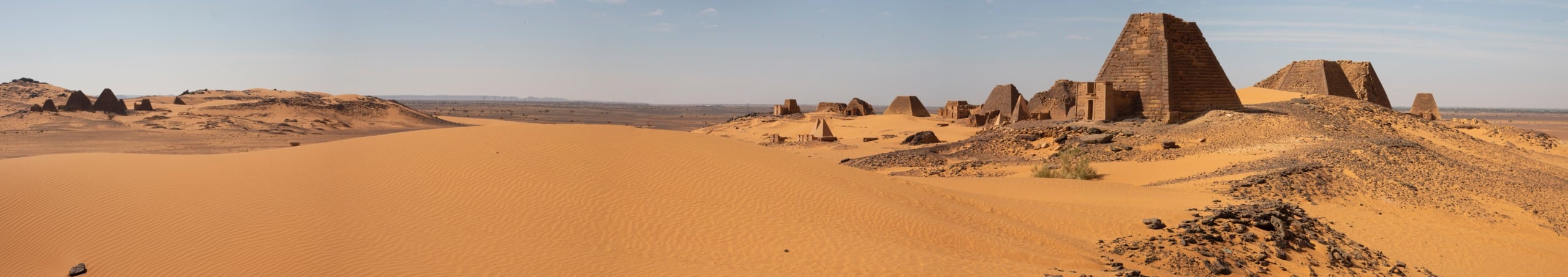

Photo by Erik Hathaway on Unsplash

District courts and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia have recently issued opinions addressing constitutional issues in litigation against Sudan.

The United States and the Republic of Sudan signed an agreement (the Claims and Dispute Resolution Agreement) designed to improve diplomatic relations between the two countries, to promote democracy in Sudan, and to settle claims against Sudan. It entered into force in February 2021. The preamble specifically mentions the 1998 bombings of U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and the 2000 attack on the U.S.S. Cole, but the operative language in Article II extends more broadly to preclude suits by U.S. and foreign nationals caused by terrorist acts “occurring outside of the United States of America and prior to the date of execution of this Agreement.” This language makes the agreement inapplicable to litigation against Sudan for its alleged involvement in the 9/11 attacks because those occurred inside the United States. The Annex lists specific cases involving other terrorist attacks allegedly supported by Sudan that are covered by the Agreement.

In exchange for its agreement to preclude some terrorism-related lawsuits against Sudan, the United States received a lump sum payment of $335,000,000. The Agreement makes clear that the United States has “espoused” the claims of the U.S. nationals against Sudan and that those claims may no longer be pursued in U.S. courts. The Annex to the agreement provides for the creation of a Commission that will make awards to claimants who are not U.S. nationals, but whose claims in U.S. courts were terminated through the Agreement. The United States formally lacks the power to espouse those claims. Payments to U.S. claimants have ranged from $170,000 to $10 million.

The Agreement raises a handful of constitutional issues, while litigation against Sudan related to 9/11, which is not covered by the Agreement, has raised others.

Constitutional Issues and Claim Settlement

Espousal allows the president to settle claims of U.S. nationals against a foreign state, even without the consent of the injured parties, who may have hoped for a much larger verdict in their favor. As some readers will know, the claim settlement practice of the United States dates back to 18th century, and was challenged on constitutional grounds in Dames & Moore v. Regan(1981).

In Dames & Moore, the claim settlement agreement with Iran (the Algiers Accords), which was integral to resolving the hostage crisis of 1979, was challenged in part as exceeding the president’s power because it terminated existing litigation not through a treaty or a federal statute but instead through a sole executive agreement. The Agreement with Sudan is not open to that challenge: it was implemented through a federal statute, the Sudan Claims Resolution Act. The legislation restored Sudan’s sovereign immunity, so that the terrorism exception under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act no longer applies to Sudan. The plaintiffs in Dames & Moore also argued that the Algiers Accords and the termination of their claims were unlawful under the Fifth Amendment because they constituted a taking without just compensation; the Supreme Court rejected that claim as unripe.

The Agreement with Sudan has been challenged by plaintiffs whose did not receive a pay-out from the settlement but whose terrorism-related cases against Sudan were dismissed pursuant to the Agreement and the Act. For example, a family who was the victim of an attack in Israel allegedly perpetrated by Hamas with the support of Sudan, is no longer able to bring their claim in U.S. courts, but they have not received any compensation from the settlement. They argued, in Mark v. Republic of Sudan, that the small group of “Hamas Victims” have suffered violations of their Fifth Amendment right to equal protection and their constitutional right of access to courts. The United States intervened in support of Sudan.

The plaintiffs’ opening brief to the Court of Appeals in Mark argued that the decision not to compensate them “cannot be reconciled with” the “articulated purposes” of the Agreement and the Act. Contrary to the articulated purposes of promoting “justice, transparency, and accountability,” plaintiffs argue, “the Settlement Agreement and Act were negotiated secretly and exclusively in consultation with private lawyers for the favored claimants and for the benefit of their clients alone. As a result, the Settlement Agreement divides the settlement proceeds among only certain specified victims and the Act expressly provides lump sum payments for others.”

The Second Circuit held for Sudan, reasoning in large part that the Act’s distinction between the 9/11 plaintiffs and the Hamas plaintiffs is rational because:

The Act’s carveout for September 11 victims and families involves one of the most fatal attacks on the United States homeland. And the litigation surrounding September 11 has been ongoing for nearly twenty years. The Marks’ claims, on the other hand, stemmed from a terrorist attack abroad, and their suit arose just a few months before the United States and Sudan entered into the Agreement. It was rational for the Act to maintain decades-old claims over more recent ones and to prioritize attacks on the homeland over other attacks

The opinion also cites the long history of claim settlement and Congress’s broader power to determine the subject matter jurisdiction of the federal courts. Because the Act restores Sudan’s immunity under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) in cases like Mark, the courts lack subject matter jurisdiction. A district court opinion in a different case, Steinberg v. Republic of Sudan, reached the same result for similar reasons.

Constitutional Issue in the 9/11 Litigation

The 9/11-related cases against Sudan also raise an important constitutional issue addressed by Judge Daniels in an opinion from August 10, 2023. Sudan is not entitled to immunity under the FSIA for the 9/11 claims because the terrorism exceptions apply. Because those exceptions apply, and because the Sudan has been properly served, there is a statutory basis for the exercise of personal jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1330(b). That leaves the question of whether the exercise of personal jurisdiction by a federal court over Sudan is consistent with due process.

Judge Daniels answered yes. He may well be correct, but not for the reasons provided in the Second Circuit case that he cites, Frontera Resources Azerbaijan Corp. v. State Oil Co. of Azerbaijan Republic. As I have explained elsewhere, that case erroneously held that foreign states lack Fifth Amendment due process rights. To be sure, Judge Daniels is bound by Second Circuit precedent. Moreover, personal jurisdiction might be constitutional for other reasons, such as satisfaction of a minimum contacts test, or because Fifth Amendment due process imposes no limitations on personal jurisdiction beyond what Congress provides. But the entitlement of foreign states to due process protections is an important question that arises in a variety of contexts. Hopefully the Second Circuit will revisit the issue.