Throwback Thursday: Joseph Story and the Comity of Nations

May 5, 2022

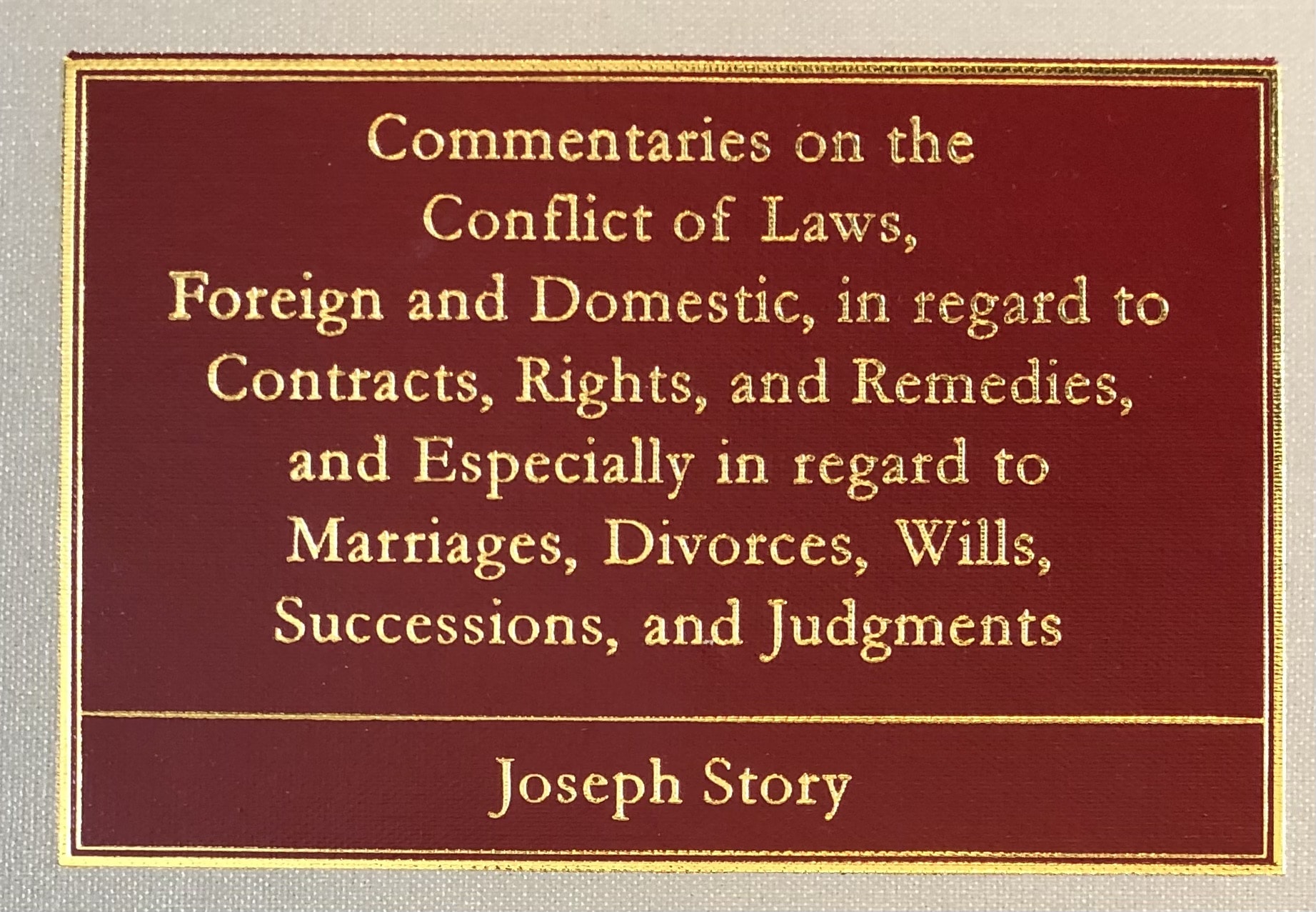

One of the most influential books on transnational litigation was written nearly two centuries ago by a sitting Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Joseph Story’s Commentaries on the Conflict of Laws, first published in 1834, synthesized foreign and domestic cases regarding conflict of laws and the enforcement of foreign judgments. Story endorsed international comity as the basis for domestic law in these two areas, establishing a principle that would provide the foundation for many other doctrines that are critical to litigating transnational cases in U.S. courts today.

Story’s Commentaries

Joseph Story had a CV that puts any modern jurist to shame. He became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1812 at the age of 32, the youngest person ever to hold that position, and he served on the Court for 33 years. Among his most famous opinions are Martin v. Hunters Lessee (1816), United States v. The Amistad (1841), Prigg v. Pennsylvania(1842), and Swift v. Tyson (1842). In 1829, Story also became Dane Professor of Law at Harvard University. He wrote books on bailments, equity, agency, partnership, bills of exchange, and promissory notes. But his best-known books are his 1833 Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (in three volumes) and his 1834 Commentaries on the Conflict of Laws, which he revised and expanded in 1841.

In Commentaries on the Conflict of Laws, Story wrote that the “comity of nations” was “the most appropriate phrase to express the true foundation and extent of the obligation of the laws of one nation within the territories of another.” National law was generally territorial in Story’s day, though there were exceptions for the regulation of state’s own citizens abroad and for universal offenses like piracy. In a world of territorial states, comity explained how foreign laws and foreign judgments could have effect outside the foreign state’s own borders. Such effect was critical if people were to be held to their contractual and other obligations. How much recognition to give foreign laws and judgments was for each recognizing nation to decide as a matter of its own domestic law. This was because “[n]o nation can . . . be required to sacrifice its own interests in favour of another; or to enforce doctrines which, in a moral or political view, are incompatible with its own safety or happiness, or conscientious regard to justice and duty.”

Story did not invent international comity. In the late 1600s, the Dutch jurist Ulrich Huber published a short tract on conflicts, De Conflictu Legum, positing that “[s]overeigns will so act by way of comity that rights acquired within the limits of a government retain their force everywhere so far as they do not cause prejudice to the power or rights of such government or of its subjects.” Lord Mansfield embraced Huber’s principle of comity as the basis for English conflicts rules in Robinson v. Bland (1760), and early American decisions followed Huber as well. In 1797, Alexander Dallas even published a translation of Huber’s tract in U.S. Reports. Story acknowledged his debt to Huber. But it was Story’s treatise that cemented international comity into the foundations of American law.

Comity’s Spread

Within just a few years, the U.S. Supreme Court explicitly relied on comity as the basis for conflicts rules, noting in Bank of Augusta v. Earle (1839) that “by the general practice of civilized countries, the laws of the one, will, by the comity of nations, be recognised and executed in another.” Within the United States, comity was bound up with the question of slavery. Writing for the Court in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), Justice Story observed that “[b]y the general law of nations, no nation is bound to recognise the state of slavery.” If it did so, he continued, “it is as a matter of comity, and not as a matter of international right.”

At the end of the nineteenth century, in Hilton v. Guyot (1895), the Supreme Court relied on Story’s treatise to ground the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments on international comity. “The extent to which the law of one nation,” Hilton said, “whether by executive order, by legislative act, or by judicial decree, shall be allowed to operate within the dominion of another nation, depends upon what our greatest jurists have been content to call ‘the comity of nations.’”

Over time, international comity became the basis for other doctrines of transnational litigation. The first example is found in an 1822 opinion by Justice Story himself. Referring to the Supreme Court’s seminal decision a decade earlier in The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon (1812), Story observed in The Santissima Trinidad that the doctrine of foreign sovereign immunity “stands upon principles of public comity and convenience.” Today, customary international law requires states to grant immunity to foreign sovereigns in some circumstances, but the U.S. Supreme Court continues to refer to foreign sovereign immunity as a matter of “grace and comity.” To the extent that U.S. law on foreign sovereign immunity goes beyond what customary international law requires, that characterization is apt.

International comity not only shielded foreign states from suits in U.S. courts under the doctrine of foreign sovereign immunity; it also gave foreign states the privilege of bringing their own suits in U.S. courts. In The Sapphire (1870), the Supreme Court observed that to deny foreign states that privilege “would manifest a want of comity and friendly feeling.” A century later, in Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino (1964), the Court repeated that “[u]nder principles of comity governing this country’s relations with other nations, sovereign states are allowed to sue in the courts of the United States,” recognizing exceptions only for states at war with the United States or not recognized by it.

The growth of international comity doctrines continued in the twentieth century. In 1909, Justice Holmes articulated a comity-based presumption against extraterritoriality in American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., reasoning that to apply U.S. law rather than the law of the place where the conduct occurred, “would be an interference with the authority of another sovereign, contrary to the comity of nations, which the other state concerned justly might resent.” A decade later, in Oetjen v. Central Leather Co. (1918), the Supreme Court said that the act of state doctrine “rests at last upon the highest considerations of international comity and expediency.” Both the presumption against extraterritoriality and the act of state doctrine are examples of what the Supreme Court now calls “prescriptive comity,” doctrines that restrain the prescriptive jurisdiction of the United States or recognize the prescriptive jurisdiction of other nations.

More recently, international comity has influenced a range of doctrines governing adjudicative jurisdiction. The Supreme Court invoked the “risks to international comity” when it limited general personal jurisdiction in Daimler AG v. Bauman(2014). The Court has told district courts to engage in a comity analysis when considering the discovery of evidence abroad for use in U.S. courts and the discovery of evidence in the United States for use in foreign courts. Lower courts have invoked international comity as a basis for abstaining in favor of parallel foreign proceedings and, alternatively, as an important consideration in deciding whether to enjoin such proceedings.

Comity has had its critics. Judge Cardozo famously called “comity” a “misleading word” that “has been fertile in suggesting a discretion unregulated by general principles.” Professor Joseph Beale, reporter for the first Restatement of Conflicts (1934), criticized comity for suggesting that a sovereign may establish “any rule he pleases for the conflict of laws.” Story was partly to blame for the view that comity is too discretionary, having written in his treatise that “comity is, and ever must be uncertain” and “cannot be reduced to any certain rule.”

As I have argued elsewhere, this criticism of comity is largely misplaced. International comity is discretionary in the sense that its doctrines are not required by international law, so that each nation is free to decide whether to adopt them and how to shape them. But a nation that adopts international comity doctrines can formulate them as bright-line rules rather than as discretionary standards. In the United States, many doctrines of international comity—including the act of state doctrine, the rules of foreign sovereign immunity, the privilege of foreign states to bring suits in U.S. courts, and the rules governing the enforcement of foreign judgments—operate more as rules than as standards.

Story’s Influence

Joseph Story does not deserve all the credit (or all the blame) for the ways international comity has shaped the modern U.S. law of transnational litigation. But his influence is undeniable. To see this, one need only look comparatively at Continental Europe. In transnational litigation, Continental European countries face the same basic questions as the United States and have developed many rules that correspond to U.S. comity doctrines. Yet, Continental European countries do not view these doctrines as based on comity.

As I have previously written, the difference is attributable to the influence in Europe of Friedrich Carl von Savigny. In his 1849 treatise on conflicts (volume eight of his System of Current Roman Law), Savigny rejected Story’s comity of nations, which allowed each nation to decide for itself how much recognition to give foreign law, in favor of a more universal approach. Regarding the recognition of foreign law “as the result of mere generosity or arbitrary will,” Savigny wrote, “would imply that it was also uncertain and temporary.” Although Savigny was writing only about conflict of laws, his rejection of comity made it unavailable as a theoretical foundation for other doctrines of transnational litigation.

By the same measure, Joseph Story’s adoption of comity in his 1834 treatise made it available as a theoretical foundation for doctrines of transnational litigation in the United States. Over the next 188 years, international comity has influenced nearly all the doctrines that are applied in this area—from the conflict of laws and the act of state doctrine to the presumption against extraterritoriality; from the recognition of foreign judgments to abstention and antisuit injunctions; and from the privilege of foreign states to bring suits in U.S. courts to the rules of foreign sovereign immunity. American law is full of international comity doctrines. That fact is largely the result of a book that Joseph Story somehow found the time to write while he was teaching at Harvard and serving on the U.S. Supreme Court.