Throwback Thursday: Hartford Fire Insurance Co. v. California

June 22, 2023

Thirty years ago next week, the Supreme Court addressed the extraterritorial reach of U.S. antitrust laws in Hartford Fire Insurance Co. v. California. The Court reiterated that the Sherman Act applies to anticompetitive conduct abroad that causes substantial intended effects in the United States, but it divided sharply over the role of “international comity.”

Writing for a five-Justice majority, Justice Souter limited the possibility of dismissing U.S. antitrust cases on grounds of “international comity” to cases where the conduct prohibited by U.S. law was required by foreign law. It followed that the antitrust claims in Hartford would not be dismissed because U.K. law did not require the anticompetitive activity alleged in the complaint. Writing for four dissenters, Justice Scalia endorsed the multifactor balancing approach articulated in § 403 of the Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law—yes, you read that correctly—and would have dismissed the claims in deference to U.K. law.

I clerked for Justice Harry Blackmun during the Term that Hartford was decided, and I worked on the Hartfordcase. For me, it was the beginning of a long engagement with questions of extraterritoriality. I won’t reveal anything in this post that cannot be found in publicly available records, including Justice Blackmun’s papers at the Library of Congress. But I hope it may still be interesting to look back at that decision with three decades of hindsight.

The Hartford Case

Hartford was an insurance antitrust case, brought by nineteen state attorney generals, alleging that foreign reinsurance companies conspired to deny reinsurance to certain environmental insurance policies in the United States, driving those policies off the market. The foreign reinsurance companies argued that the coordination in which they engaged was lawful where it occurred, principally the United Kingdom.

The complaints were consolidated before Judge William Schwarzer in the Northern District of California. In Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America (1976), the Ninth Circuit had adopted a multifactor balancing approach to extraterritorial antitrust cases. Timberlane asked courts to weigh seven factors to decide whether to decline jurisdiction as a matter of international comity.

Judge Schwarzer dutifully applied Timberlane’s factors and dismissed the complaints, concluding “that the conflict with English law and policy which would result from the extra-territorial application of the antitrust laws in this case is not outweighed by other factors.” On appeal, the Ninth Circuit applied the same multifactor test but reversed. “A single factor points toward abstention: the conflict with a long-established British policy towards a venerable British trade, the underwriting of insurance,” the court wrote. “Every other factor—nationality, likelihood of compliance, the significance of the effects on American commerce, their foreseeability and their purposefulness—points to the appropriateness of exercising jurisdiction.”

The Controversy over Interest Balancing

The Supreme Court granted cert in Hartford because the circuits were divided. The Third Circuit followed Timberlane’s approach in Mannington Mills, Inc. v. Congoleum, Inc. (1979), but the D.C. Circuit rejected interest-balancing in Laker Airways v. Sabena (1984).

The American Law Institute had also weighed in. The Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law, published in 1987, took the position in § 403 that Timberlane’s multifactor balancing approach was required not just as a matter of international comity but as a matter of international law. Section 403 stated that even when a basis for prescriptive jurisdiction exists—such as territory, effects, or nationality—customary international law requires that the exercise of such jurisdiction not be “unreasonable.” Reasonableness was to be determined on a case-by-case basis by evaluating a list of eight factors very much like Timberlane’s. The Restatement (Third)’s assertion that international law required case-by-case balancing was controversial, however, and was challenged by the State Department’s Legal Adviser, among others.

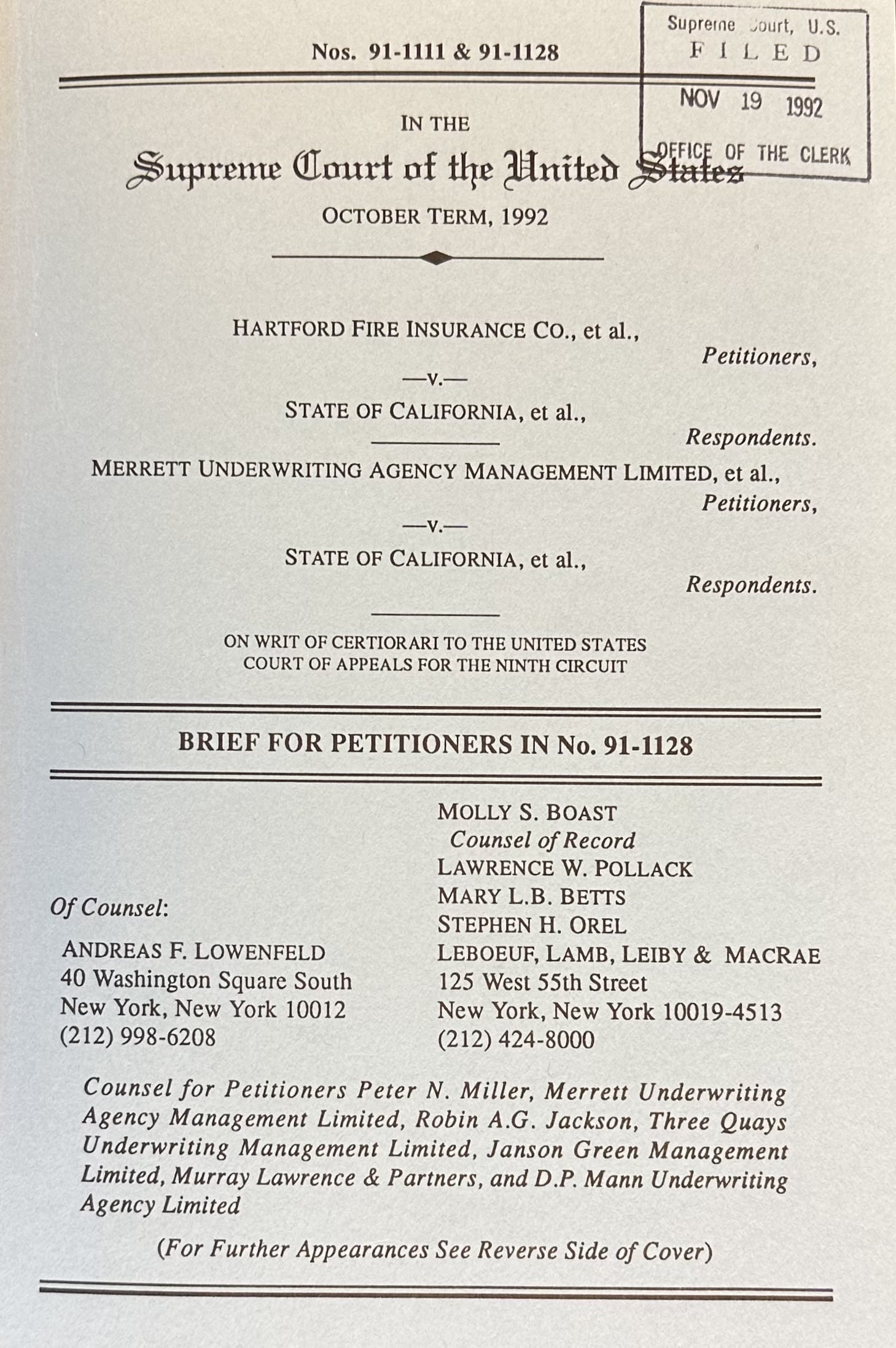

Hartford became a test for the Restatement (Third)’s approach to extraterritoriality. Professor Andreas Lowenfeld, who was the Associate Reporter responsible for drafting § 403, served as counsel for some of the petitioners. Their brief “urged this Court to endorse expressly the principles of international law and comity developed to date by scholars and in the opinions of lower courts, which require moderation in the exercise of jurisdiction to apply U.S. law.” A separate brief for one of the petitioners likewise urged the Court to dismiss the case on grounds of international comity, while a third brief addressed the question whether the McCarran-Ferguson Act (exempting insurance companies from U.S. antitrust laws) immunized the defendants.

Canada and the United Kingdom each filed an amicus brief in support of petitioners. The United Kingdom endorsed the Restatement (Third)’s position that, under international law, a state may not exercise jurisdiction “when to do so would be unreasonable, after evaluating and balancing all the factors.” Canada also argued from the perspective of international law but took the position that territorial jurisdiction always prevails in the case of conflict. “As a jurisdictional issue,” Canada said, “conflicts of law should not be ‘weighed’ or ‘balanced’ against other national or international interests.”

The state attorneys general countered that, under the Supreme Court’s past decisions, the Sherman Act applies to foreign conduct that causes substantial, intended effects in the United States. “A vague multi-factor test,” they continued, “would not provide a useful addition to this Court’s precedents.” The case presented no conflict with foreign law, the states argued, because English law did not compel the petitioners’ anticompetitive conduct.

In an amicus brief for the United States, the Solicitor General endorsed Timberlane’s general approach but argued that a conflict with foreign law, for purposes of international comity, exists only if a foreign government has directed the defendants to engage in the anticompetitive conduct or their failure to do so would have frustrated clear policies of the foreign government.

A Divided Supreme Court

By a vote of 5-4, the Supreme Court declined to endorse the Restatement (Third)’s interest-balancing approach to international comity. Writing for the majority on this question, Justice Souter began by observing that “it is well established by now that the Sherman Act applies to foreign conduct that was meant to produce and did in fact produce some substantial effect in the United States.” He found it unnecessary to decide whether a court could properly decline to exercise jurisdiction on grounds of international comity, however, because in this case there was no “true conflict” with foreign law. Justice Souter adopted the Solicitor General’s definition of conflict, holding that there was no conflict for comity purposes because British law did not require what U.S. law prohibited. Although the Court did not definitively reject § 403’s approach, the Court narrowed its application to conflicts like this.

Justice Scalia, writing for four, dissented on this question. Invoking the Charming Betsy canon, he argued that the Sherman Act should be interpreted not to violate “customary international-law limits on jurisdiction to prescribe.” He looked to § 403 of the Restatement (Third) for customary international law.

The “reasonableness” inquiry turns on a number of factors including, but not limited to: “the extent to which the activity takes place within the territory [of the regulating state],” id., § 403(2)(a); “the connections, such as nationality, residence, or economic activity, between the regulating state and the person principally responsible for the activity to be regulated,” id., § 403(2)(b); “the character of the activity to be regulated, the importance of regulation to the regulating state, the extent to which other states regulate such activities, and the degree to which the desirability of such regulation is generally accepted,” id., § 403(2)(c); “the extent to which another state may have an interest in regulating the activity,” id., § 403(2)(g); and “the likelihood of conflict with regulation by another state,” id., § 403(2)(h).

“Rarely would these factors point more clearly against application of United States law,” he continued. “The activity relevant to the counts at issue here took place primarily in the United Kingdom, and the defendants in these counts are British corporations and British subjects having their principal place of business or residence outside the United States.” Great Britain had a “heavy” interest in regulating the activity, whereas the U.S. interest was “slight” considering the McCarran-Ferguson Act’s antitrust exemption for insurance.

For Justice Scalia, this was a remarkable opinion, embracing not only customary international law but also multifactor balancing. He once remarked of a different balancing test that the outcome depends “on which factors the judge considers and how much weight he accords each of them.” With that observation in mind, it is worth looking again at Scalia’s treatment of § 403’s factors in Hartford.

- In § 403(2) the first reasonableness factor reads: “(a) the link of the activity to the territory of the regulating state, i.e., the extent to which the activity takes place within the territory, or has substantial, direct, and foreseeable effect upon or in the territory.” In Hartford, Justice Scalia quoted the part of this that pointed to Great Britain (“the extent to which the activity takes place within the territory” of the regulating state) but not the part that pointed to the United States (“or has substantial, direct, and foreseeable effect upon or in the territory” of the regulating state).

- Section 403’s second factor reads: “(b) the connections, such as nationality, residence, or economic activity, between the regulating state and the person principally responsible for the activity to be regulated, or between that state and those whom the regulation is designed to protect.” Again, Scalia quoted the part that pointed to Great Britain (“the connections, such as nationality, residence, or economic activity, between the regulating state and the person principally responsible for the activity to be regulated”) and omitted the part that pointed to the United States (“or between that state and those whom the regulation is designed to protect”).

- As for § 403’s other factors, he quotes three having to do with state interests and conflicts and omits three others having to do with justified expectations, importance to the international system, and consistency with the traditions of the international system. He deems Great Britain’s interest in regulating the reinsurance market “heavy,” while dismissing the U.S. interest as “slight” because of the McCarran-Ferguson Act’s antitrust exemption for insurance. What he fails to mention here is that the exemption does not apply “to the extent that such business is not regulated by State Law,” and it seems questionable that the London reinsurance market is regulated by U.S. state law.

In short, Justice Scalia concluded that § 403 pointed clearly against the application of state law through selective application. He was, to quote another trenchant Scalia opinion, “look[ing] over the heads of the crowd and pick[ing] out [his] friends.”

The Missing Presumption Against Extraterritoriality

Another fact that made the opinions in Hartford remarkable was the absence of the presumption against extraterritoriality from the analysis. Just two years earlier, in the Aramco case, the Supreme Court had resurrected the presumption and applied this canon of statutory interpretation to limit Title VII to employment discrimination that occurs in the United States. (Congress quickly amended the statute to apply to discrimination against U.S. citizens abroad by U.S. companies and foreign companies controlled by U.S. companies, with an exception for discrimination that is required by the law of the country where the workplace is located.)

Justice Souter never mentioned Aramco or the presumption in his opinion for the Court. Justice Scalia’s dissent mentioned the presumption only briefly, asserting (questionably) that the Sherman Act’s applicability to conduct entirely outside the United States was settled by Supreme Court precedent. The lack of attention to the presumption against extraterritoriality is best explained by the arguments in the briefs. Only one of the three briefs for the petitioners even mentioned Aramco, and that brief made no argument for dismissing the case based on the presumption against extraterritoriality, instead resting solely on the “international comity” argument. Nor did the Solicitor General’s amicus brief mention Aramco. Only the amicus briefs of Canada and the U.K. pressed the presumption against extraterritoriality as an argument against applying the Sherman Act in Hartford.

But the disjunction between Aramco and Hartford raised questions about the scope of the presumption against extraterritoriality. If the presumption did not apply to U.S. antitrust law, what other statutes might be excluded. One young law professor argued that the cases could be reconciled with the understanding that U.S. law applies whenever conduct causes harmful effects in the United States.

The Three Decades Since

In the thirty years since Hartford was decided, the Supreme Court has not returned to consider whether international comity allows U.S. courts to abstain from applying U.S. law extraterritorially based on a case-by-case weighing of factors like those in Timberlane and § 403. Justice Scalia subsequently abandoned his uncharacteristic embrace of multifactor balancing, writing in Spector v. Norwegian Cruise Line (2005) that “fine tuning” the geographic scope of federal legislation “through the process of case-by-case adjudication is a recipe for endless litigation and confusion.” The Supreme Court also cast doubt on § 403’s case-by-case approach in another extraterritorial antitrust case, F. Hoffman-La Roche v. Empagran S.A. (2004), calling it “too complex to prove workable.”

Instead of relying on multifactor balancing tests, the Supreme Court has, over the past three decades, repeatedly applied the presumption against extraterritoriality to determine the geographic scope of federal statutes. In 2010, Morrison v. National Australia Bank substantially revised the presumption. The new presumption against extraterritoriality is more flexible because it recognizes that the geographic scope of a statutory provision may depend on its focus. But this flexibility operates provision-by-provision, not case-by-case.

In 2018, the Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law abandoned § 403’s multifactor balancing test. The Restatement (Fourth) found that “state practice does not support a requirement of case-by-case balancing to establish reasonableness as a matter of international law” (§ 407, reporters’ note 3). The Restatement (Fourth)did adopt a principle of “reasonableness in interpretation” (§ 405) as a matter of domestic law, based on the Supreme Court’s decision in Empagran. But this principle is significantly narrower than old § 403.

How to Read Hartford Today

Hartford still stands for the proposition that U.S. antitrust law applies to foreign conduct that causes substantial, intended effects in the United States. (The United States is not alone in applying an effects approach to competition law; both the European Union and China do the same.) It is possible to view this effects approach as an exception to the presumption against extraterritoriality based on precedent, as Justice Scalia did in Hartford. It is also possible to harmonize Hartford with Morrison by recognizing that the focus of U.S. antitrust laws is anticompetitive effects, so that these laws would apply when anticompetitive conduct abroad causes effects in the United States.

Some lower courts have read Hartford as endorsing Timberlane’s case-by-case approach to international comity, albeit with a threshold requirement of establishing a “true conflict” with foreign law. In the Vitamin Ccase, the Second Circuit dismissed price-fixing claims against Chinese companies on the ground that Chinese law required them to coordinate prices. As I have explained previously, I believe this decision misreads Hartford and is inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s precedents. Unfortunately, the Court declined the chance to review the case.

The better way to read Hartford is as an endorsement of the doctrine of foreign state compulsion, under which U.S. courts may excuse violations of U.S. law that are compelled by foreign law. But as articulated by the Supreme Court in the Rogers case and restated in § 442 of the Restatement (Fourth), this doctrine requires the party raising it to show that they are likely to suffer severe sanctions for failing to comply with foreign law and that they acted in good faith to try to avoid the conflict. Neither showing was made in Vitamin C.

Conclusion

Hartford Fire Insurance v. California remains the Supreme Court’s leading decision on the extraterritorial application of U.S. antitrust laws. But Hartford ducked the international comity question, and thirty years later Timberlane’s approach continues to cause mischief in the lower courts. Hopefully, it will not take another thirty years for the Supreme Court to answer that question and put Timberlane to rest.