Does China Have to Pay Qing Dynasty Bonds?

November 4, 2025

China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing, fell in 1912. But some bondholders have not given up trying to collect on bonds issued as long ago as 1898. The latest attempt claims that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) violated priority clauses in these old bonds when it issued dollar-denominated bonds in 2020 and 2021, some of which were sold to institutional investors in the United States.

On September 15, 2025, in Noble Capital LLC v. People’s Republic of China, Judge Amir Ali (District of the District of Columbia) held that the PRC was immune from suit under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). The FSIA’s commercial activity exception did not apply, he reasoned, because the claims were not based upon a commercial act in the United States. And the FSIA’s waiver exception did not apply because the waiver of immunity in the new bonds did not extend to claims for nonpayment of the old bonds.

The Old Bonds

Between 1898 and 1913, China issued sovereign bonds to finance war indemnities, government functions, and railroads. These bonds were secured by customs revenues and other taxes and provided (in language that differs a bit from bond to bond) that the loans “shall have priority both as regards to principal and interest over all future loans” and that no future loan “shall take precedence of or be on an equality with this loan.”

Before 1912, such bonds were issued by the Imperial Government of China. After the Qing Dynasty fell in 1912, they were issued by the new Republic of China. The Republic of China made principal and interest payments until 1939, and it reaffirmed its payment obligations in 1947. But following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, China repudiated the bonds.

Over the years, there have been various attempts to hold the PRC liable for the old bonds. In 1984, a federal district court in Alabama held in Jackson v. People’s Republic of China that such claims were barred by China’s sovereign immunity, reasoning that the FSIA and its exceptions did not apply retroactively. After the Supreme Court held in 2004 that the FSIA does apply retroactively, new claims were brought but again rejected on sovereign immunity and statute of limitations grounds.

The New Bonds

In 2017, China began to issue dollar-denominated bonds in order to set an interest-rate curve that would make it easier for state-owned enterprises to borrow in dollars. The first bonds were exempt from registration with the U.S. Security Exchange Commission because they were sold outside the United States in reliance on U.S. Regulation S. In 2020, China began to rely on another exemption, Rule 144A, which permits sales to institutional investors in the United States without registration.

Unlike the old bonds, the 144A bonds are unsecured obligations for which the PRC pledged no collateral. As is typical with sovereign debt, the PRC waived its sovereign immunity with respect to “any suit, action or proceedings arising out of or in connection with the Bonds” (except for actions based on federal or state securities laws).

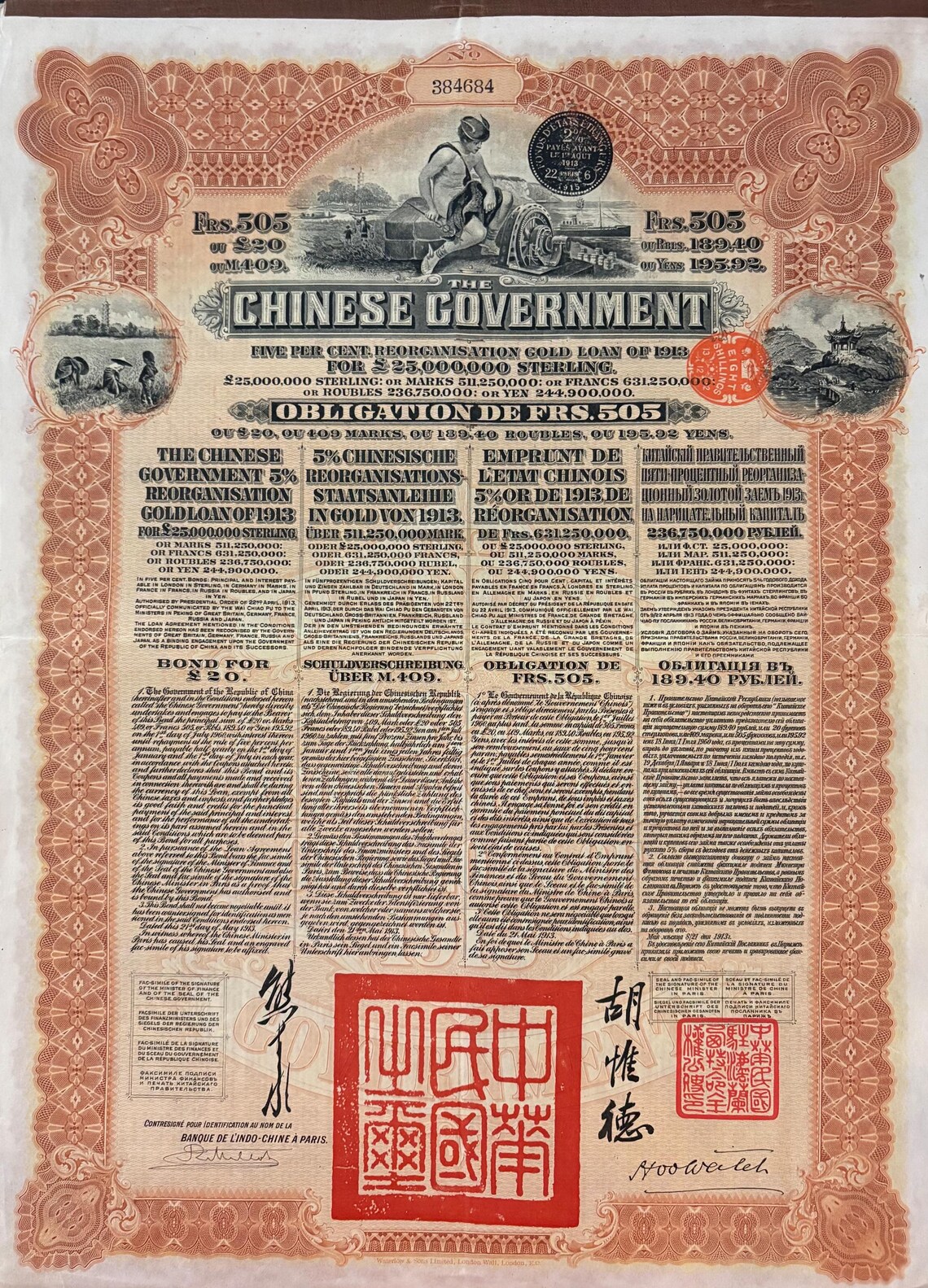

In 2023, Noble Capital sued the PRC for breach of contract, seeking more than $11.5 billion in damages. Noble Capital was incorporated under Delaware law just a month before filing suit. It is not clear when or how Noble acquired the old bonds, but they are sold as collectibles on the internet (like the example pictured, which I found on Etsy). Noble claimed that issuing the new bonds violated the priority provisions of the old bonds. Noble argued that China was not immune from suit under the FSIA (1) because its claims were based on a commercial activity carried on in the United States, specifically the sale of 144A bonds to institutional investors, and (2) because its claims were “in connection with” the new bonds and thus fell within the PRC’s waiver of immunity.

The Commercial Activity Exception

The FSIA’s commercial activity exception, 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2), provides that a foreign state shall not be immune from suit in any case

[1] in which the action is based upon a commercial activity carried on in the United States by the foreign state; or [2] upon an act performed in the United States in connection with a commercial activity of the foreign state elsewhere; or [3] upon an act outside the territory of the United States in connection with a commercial activity of the foreign state elsewhere and that act causes a direct effect in the United States.

Noble Capital relied on the exception’s first clause.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that issuing sovereign debt is a commercial activity, and it seems clear that some of the 144A bonds were sold in the United States. But was Noble’s action “based upon” that commercial activity or upon China’s nonpayment of the old bonds?

In OBB Personenverkehr AG v. Sachs (2015), the Supreme Court held “that an action is based upon the particular conduct that constitutes the gravamen of the suit.” In that case, the plaintiff, who purchased a Eurail pass in the United States, was badly injured at a train station in Austria. The gravamen of the plaintiff’s suit, the Court explained, was not the purchase of the Eurail pass but rather the “tragic episode in Austria, allegedly caused by wrongful conduct and dangerous conditions in Austria, which led to injuries suffered in Austria.”

Noble Capital argued that its claims were based upon the issuance of the 144A bonds, which allegedly violated the priority clauses in the old bonds. But Judge Ali saw it differently.

Here, the gravamen of Noble Capital’s suit—the act that actually injured them—is the nonpayment of interest and principal on the historical bonds. The injury, and the more than $11.5 billion in damages sought as relief in this case, stem from Noble Capital’s ownership of the historical bonds; the terms and conditions upon which those historical bonds were issued, including the guarantee of priority and precedence; and the failure to pay the principal or interest on the loans for nearly a century, including the PRC’s continued repudiation of the loans.

Because “the issuance of the historical bonds and failure to pay principal and interest on them were carried on in China, not the United States,” the FSIA’s commercial activity exception did not apply.

The Waiver Exception

The FSIA’s waiver exception, 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(1), further provides that a foreign state is not immune from suit in any case “in which the foreign state has waived its immunity either explicitly or by implication.” The D.C. Circuit has heldthat “a foreign state explicitly waives its sovereign immunity in a treaty or contract only if it clearly and unambiguously agrees to suit.”

Noble Capital pointed to the waiver of immunity in the new 144A bonds, noting that it referred not just to suits “arising out of” the new bonds but also to suits “in connection with” them. But Judge Ali found it hard to see the connection.

Noble Capital’s claims are all premised on breach of the terms of the historical bonds, not breach of the terms of any bonds issued in 2020 or 2021. And it would be difficult to conclude that an action based on the historical bonds arises “in connection with” the new bonds when, according to the complaint, the PRC repudiated the historical bonds nearly 70 years earlier, and multiple times thereafter.

The phrase “in connection with” may be broad. But it still requires a connection between the new bonds and the old ones, which is missing here.

Conclusion

Although Judge Ali was right to dismiss Noble Capital’s case on immunity grounds, it is worth noting that China also has good defenses on the merits. The last of the old bonds matured in 1960, and even D.C.’s most generous statute of limitations would have run in 1972.

It is also not at all clear that issuing the new bonds violated the terms of the old. The new bonds are unsecured and thus do not have “priority” or “precedence” over the secured old bonds. Nor do the new bonds impair bondholders’ security in the customs revenues and taxes that China pledged for the old bonds (revenues that in at least some cases no longer exist). Absent language not found in the old bonds, courts in the United States have not treated pari passu clauses as establishing equal payment obligations.

Although these arguments go to the merits, they tend to support Judge Ali’s conclusion with respect to waiver. The new bonds have literally nothing to do with the old ones.

Noble Capital has appealed.