The Challenges of Suing Under JASTA

May 15, 2024

Foreign states may be sued in the United States only to the extent permitted by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). Over the years, Congress has amended the statute to create several exceptions to immunity for terrorism-related lawsuits, especially for those brought against states designated as “state sponsors of terrorism.” But only a very small number of countries have been so designated. The FSIA’s terrorism exceptions were expanded by an Obama-era statute – Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) (28 U.S.C. § 1605B) – allowing for suits against any foreign state for certain terrorism-related conduct. Because JASTA was drafted with lawsuits related to the September 11, 2001, attacks in mind, it only permits suits for terrorist attacks in the United States – a very significant limitation. Even for terrorism in the United States, the requirements JASTA can be difficult to satisfy, as a recent district court case, Watson v. Arabia, illustrates.

Background

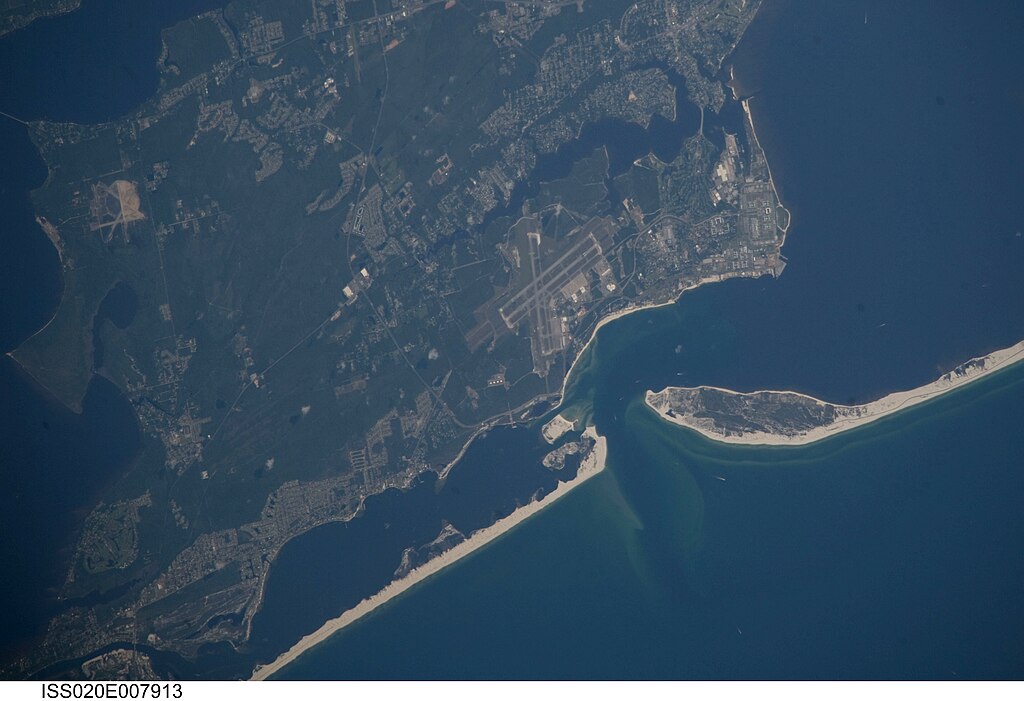

On December 6, 2019, Mohammad Saeed Al-Shamrani conducted a terrorist attack at the Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola in Pensacola, Florida. Three members of the U.S. Navy were killed, as was Al-Shamrani. Others were injured. Al-Shamrani, a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Saudi Air Force, had been stationed at NAS Pensacola as part of a cooperative training program. He joined the Royal Saudi Air Force (“RSAF”) in 2015, arrived in the United States on in 2017, and began his training at NAS Pensacola in May 2018. In July 2019, the complaint alleges, Al-Shamrani used a hunting license to purchase a handgun that he kept on base in violation U.S. and Saudi Arabian policies. After the attack, the FBI discovered from Al-Shamrani’s phone data that he had been in contact with Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (“AQAP”). Victims sued the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for its involvement in the attack, arguing that Saudi Arabia was not immune from suit under JASTA’s amendments to the FSIA. Judge M. Casey Rodgers (N.D. Fla.) disagreed.

JASTA creates an exception to the immunity if plaintiffs seek: “money damages … against a foreign state for physical injury to person or property or death occurring in the United States and caused by—

(1) an act of international terrorism in the United States; and

(2) a tortious act or acts of the foreign state, or of any official, employee, or agent of that foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her office, employment, or agency, regardless where the tortious act or acts of the foreign state occurred.”

In order to satisfy the statute, the plaintiffs had to show that a tortious act was committed by Saudi Arabia or by a Saudi Arabian employee acting within the scope of his employment and that the act caused the plaintiffs’ injuries. The plaintiffs made three arguments to meet this burden.

Scope of Employment

First, the plaintiffs alleged that Al-Shamrani was acting within the scope of his employment because he conducted the attack on a U.S. Navy base where he was training, while he was in uniform and with a belief that he was acting in service to his country. Even accepting the truth of these allegations, the court disagreed that A-Shamrani was acting within the scope of his employment.

Because the attack occurred in Florida, the court applied Florida law. Under Florida tort law, the scope of employment inquiry requires the conduct to be (1) “the kind for which the employee was employed to perform,” (2) “occurred within the time and space limits” of employment, and (3) was “activated at least in part by a purpose to serve the employment.” Al-Shamrani’s attack occurred during his time on base while training, so it satisfies the second requirement. The court found the first and third parts of the test were not satisfied because “neither the act itself nor the alleged belief by Al-Shamrani that he was serving his employer is grounded in any work-related task or duty of an RSAF member participating in a cooperative training program as a flight trainee at NAS Pensacola, where he was not authorized to possess a weapon.” Although the scope of employment inquiry can be satisfied if the employee’s intentional tort “bears a close nexus to the workplace, to a work-related duty,” the court reasoned that Al-Shamrani’s “murderous attack” was “so extreme” as to be outside of his employment as a matter of law.

Vicarious Liability

Second, the plaintiffs alleged that Saudi Arabia should be vicariously liable for the actions of Al-Shamrani because of its negligence in its vetting and supervision of Al-Shamrani. RASF allegedly failed to properly screen Al-Shamrani for his radical beliefs before he joined the RSAF — beliefs that were apparent from his social media activity. RASF also allegedly failed to provide adequate oversight of Al-Shamrani’s activities after he arrived in the United States.

The court rejected this claim, reasoning that JASTA is not satisfied by allegations that a foreign state was negligent by omission. JASTA does not subject a foreign state to “the jurisdiction of the courts of the United States under subsection (b) on the basis of an omission or a tortious act or acts that constitute mere negligence.” The district reasoned that the word “omission” “stands on its own,” so that even an omission that constitutes reckless behavior or gross negligence would not satisfy the statute. Plaintiffs’ allegations in the complaint, the court concluded “are all phrased as a failure of the foreign state and/or its agent(s) to do something, which does not satisfy JASTA.”

Material Support of Terrorism

And third, the plaintiffs argued that Saudi Arabia committed tortious acts by harboring and materially supporting a terrorist (Al-Shamrani) through funding, weapons, and training. They also allege that Saudi Arabia materially supported AQAP by fighting with it against the Houthis in Yemen. The court rejected the claim regarding material support for Al-Shamrani because the only support afforded to Al-Shamrani was through his job as an RSAF member, which was not sufficient to establish proximate causation between Saudi Arabia’s conduct and the NAS Pensacola attack.

As to the AQAP claim, plaintiffs argued that it was reasonably foreseeable that material support to AQAP in the war against the Houthis could lead to attacks in the United States. The court held to the contrary, reasoning that the alleged connections were “too remote and tenuous” to establish that Saudi Arabia’s “actions were a ‘substantial factor in the sequence of events’ leading to the NAS Pensacola attack or that the attack was ‘reasonably foreseeable’ to Saudi Arabia based on its activities in connection with Yemen.”

Other Exceptions to the FSIA

The plaintiffs also argued that the FSIA’s noncommercial tort, commercial activity, and waiver exceptions applied. The noncommercial tort exception does not extend to “discretionary acts,” which include the hiring and supervision of employees. The commercial activity exception does not apply because the cooperative training relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia was not “commercial.” Finally, the waiver exception was rejected because there was inadequate support for the claim that the contractual relationship between Saudi Arabia and the United States involved a waiver of immunity. The court denied discovery to permit the plaintiffs access to the actual agreements between the United States and Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

Suing a foreign state under JASTA requires not only an act of international terrorism in the United States but also an adequate connection between the terrorism and the foreign sovereign itself. Even if a foreign government employs someone with open ties to a terrorist organization, that standard can be hard to satisfy.