A Primer on Forum Selection Clauses

March 26, 2022

Imagine Generated by Gemini

A forum selection clause is a contractual provision that selects a specific court to resolve disputes. When suit is filed in a court that is not the chosen forum, the clause may provide a basis for dismissal or transfer. When suit is filed in the chosen forum, the clause may provide a basis for the assertion of personal jurisdiction over the defendant.

Purpose

One purpose of a forum selection clause is to reduce litigation uncertainty by prospectively selecting a forum in which to resolve future disputes. Another purpose is to confer a tactical advantage on the party whose home jurisdiction is chosen as the exclusive forum. Still another purpose is to select a body of procedural law. As a rule, choice-of-law clauses do not select the procedural law of the jurisdiction named in the clause. By selecting a specific court to resolve disputes, a forum selection clause operates to select the procedural law of that jurisdiction. Yet another purpose of a forum selection clause is to facilitate the assertion of personal jurisdiction over out-of-state defendants. If a defendant agrees to litigate in the courts in a particular state, it consents to personal jurisdiction there.

History

Forum selection clauses can be found in employment contracts for sailors as early as 1795. Although these provisions were sometimes enforced by federal courts sitting in admiralty, most U.S. courts declined to give effect to these provisions throughout the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries. When an insurance company sought to enforce a forum selection clause in 1856, for example, the Massachusetts Supreme Court refused to do so. In 1874, the U.S. Supreme Court held that “agreements in advance to oust the courts of the jurisdiction conferred by law are illegal and void.” In light of these and other similar decisions, it is no surprise that forum selection clauses rarely appear in U.S. contracts drafted prior to 1950.

In the 1960s and 1970s, judicial attitudes began to shift. The Model Choice of Forum Act, promulgated in 1968, directed courts to enforce forum selection clauses under most circumstances. Section 80 of the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws, published in 1971, adopted a similar position. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision upholding a forum selection clause in The Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Company ushered in a sea change in the treatment of these provisions. In the years to come, most state and federal courts came around to the view that forum selection clauses were presumptively enforceable. Perhaps as a result, the percentage of U.S. contracts that contain forum selection clauses has crept upward over the past several decades. This upward trend has been particular pronounced in international agreements.

Interpretation and Drafting

Virtually every word in the forum selection clause has a hidden meaning. There are five issues that are routinely litigated with respect to these provisions: (1) choice of law, (2) exclusivity, (3) scope, (4) effect on third parties, and (5) state vs. federal court.

Choice of Law. There is no general federal common law of contracts. It follows that the meaning of the language in a forum selection clause must be determined by reference to state contract law. When a contract contains both a choice-of-law clause and a forum selection clause, the courts should apply the interpretive rules of the jurisdiction selected in the choice-of-law clause to interpret the forum selection clause. When a contract omits a choice-of-law clause, the courts should perform a choice-of-law analysis to identify the law that governs the contract. Once this law is identified, the court should apply the interpretive rules of that jurisdiction to interpret the forum selection clause.

Exclusivity. An exclusive forum selection clause states that litigation shall occur in the chosen court to the exclusion of all other courts. A non-exclusive clause states that litigation may occur in the chosen court but does not foreclose the possibility of litigation elsewhere. The general rule, followed by courts across the United States, is that a clause is presumptively non-exclusive. This presumption may be overcome, however, if the clause contains so-called “language of exclusivity.” A clause contains language of exclusivity if it states that litigation “must” be brought in the chosen court or that it may “only” be brought in that court. Similarly, a clause that provides that the chosen court shall be the “sole” forum or that that court shall have “exclusive” jurisdiction contains language of exclusivity. If a clause merely states that the parties “submit” or “consent” to jurisdiction in the chosen court, by contrast, it will be deemed non-exclusive because it lacks the requisite language of exclusivity. Similarly, if a clause states that claims “may” be brought in the chosen court or it shall have “non-exclusive” jurisdiction, then the clause is non-exclusive. A court is much more likely to invoke a forum selection clause as a basis for dismissing or transferring the case to the chosen court if the clause is exclusive.

Scope. When one contracting party sues the other for fraud (a tort claim) or for unfair and deceptive trade practices (a statutory claim), the court must evaluate whether these non-contract claims are covered by a contractual forum selection clause. Some clauses are drafted in a way that makes this task easy. When a clause states that the courts of a particular state shall have exclusive jurisdiction to hear claims arising out of “the relationship between the parties,” for example, there is no need for further analysis. Such a clause clearly covers non-contract claims. Similarly, when the parties select a court to resolve claims “relating to” or “arising in connection with” the contract, there is little doubt that this clause covers non-contract claims that have some connection to the agreement.

When clauses do not contain such express language, the interpretive task is more difficult. Some clauses merely state that claims “arising out of” the agreement shall be brought in a particular court. In other cases, the clause states that the chosen courts shall have exclusive jurisdiction to hear claims “arising hereunder.” When the text of the clause provides so little guidance as to its intended scope, the courts must do the best they can to determine the likely intent of the parties.

The courts have yet to coalesce around a single interpretive rule to deal with clauses that are ambiguous with respect to their scope. Some courts take the position that such non-contract claims are never covered by a generic forum selection clause because such claims do not originate in the contract. Other courts have held that non-contract claims come within the ambit of a generic forum selection clause if they arise out of the same operative facts as a parallel claim for breach of contract. Still other courts take the position that non-contract claims are covered by generic forum selection clauses when it is necessary to refer back to the contract in order to resolve these claims. Finally, some courts have adopted a hybrid approach that combines one or more of the interpretive rules set forth above. A survey of these interpretive approaches can be found here.

Effect on Third Parties. The question of whether a forum selection clause binds individuals who did not sign the agreement containing the clause is discussed here and here. Over the past several decades, courts in the United States have gradually come around to the view that a forum selection clause may be invoked by or against a non-signatory if that person is so “closely related” to the transaction that it was “foreseeable” that the non-signatory would bound by the clause. The use of the “closely related” test is unproblematic when a non-signatory is actively seeking the benefits conferred by the clause. When the test is used to assert personal jurisdiction over a non-consenting, non-signatory defendant, however, its use arguably violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In such cases, the court must find an alternative doctrine (e.g., alter ego, third-party beneficiaries, equitable estoppel) to bind the defendant to a clause in a contract that it never signed.

The courts have generally held that non-signatories may not take advantage a forum selection clause if the contract contains a no third-party beneficiaries clause like this one:

This Agreement is intended for the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective permitted successors and assigns, and is not for the benefit of, nor may any provision hereof be enforced by, any other person.

When such a clause appears in the contract, the forum selection clause may not be invoked by a non-signatory because the clause clearly indicates that the parties did not intend for the forum selection clause to benefit anyone who was not a party to the agreement.

State vs. Federal Court. Some forum selection clauses provide that disputes must be resolved in state court to the exclusion of federal court. Other clauses provide that disputes must be resolved in federal court to the exclusion of state court. Still other clauses specify that disputes may be resolved in either state or federal court. In instances where the clause does not clearly address this issue, the courts must interpret the clause to determine whether the parties meant to select the state courts, the federal courts, or both.

Forum selection clauses that purport to vest exclusive jurisdiction in federal courts are rare. This is because federal courts are courts of limited subject-matter jurisdiction. If a forum selection clause calls for all disputes to be resolved in federal court, and if that court lacks subject-matter jurisdiction over the dispute, then the clause will have no effect. Forum selection clauses that purport to vest exclusive jurisdiction in state courts are far more common.

When a clause is ambiguous on this issue, a court must ascertain the intent of the parties. The federal courts typically begin their analysis by noting that any waiver of the right to remove a case to federal court must be “clear and unequivocal.” Over the years, the federal courts have developed canons of construction to help them answer this question in the context of forum selection clauses. A clause which provides that disputes must be resolved in the courts “of” a given state is usually interpreted to select the state courts to the exclusion of the federal courts. A clause which provides that disputes must be resolved in the courts “in” a particular state, by contract, is typically interpreted to select the state and the federal courts in that state.

When a clause calls for disputes to be resolved “in” a county rather than a state, the courts have held that the case may be heard in federal court if there is a federal courthouse physically located in that county. In one well-known case, the parties to a contract chose Nassau County, New York, as the venue in which to resolve any disputes. At the time the contract was signed, there was a federal courthouse in Nassau County. In the intervening years, however, the federal courthouse in Nassau County closed and the court was relocated to a building in Suffolk County. The issue in the case was whether the forum selection clause selecting Nassau County contemplated the possibility of litigation in federal court. The Second Circuit held that since there was no bricks-and-mortar federal courthouse located in Nassau County at the time of the suit, the forum selection clause did not allow the federal courts to hear the case and remanded it for trial in state court.

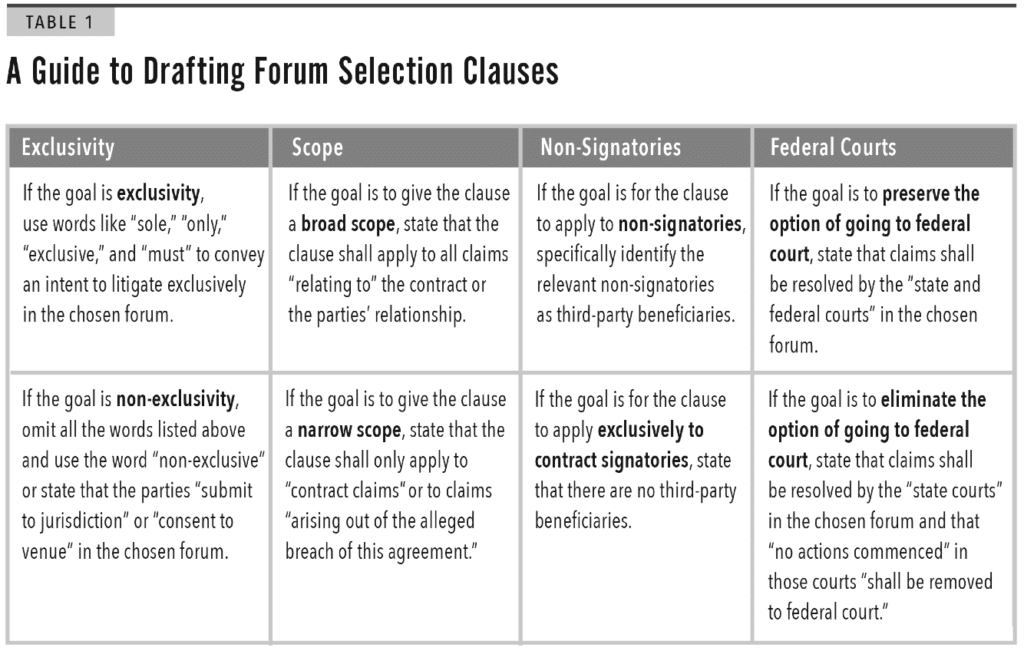

Drafting Tips. If you are in a strong negotiating position and want to lock in the courts of your home jurisdiction, you will want to draft one type of forum selection clause. If you are in a weak negotiating position and want to limit the impact of the forum selection clause, you will want to draft a different type of clause. The following chart provides some guidance as to which words and phrases are best calculated to obtain the desired outcome.

Validity

A forum selection clause is a contractual provision. Accordingly, such a clause must be valid as a matter of contract law in order for it to have any effect on the rights and obligations of the parties. The key issues relating to validity are: (1) choice of law, (2) general rules of contract, and (3) special rules of contract that apply only to forum selection clauses. Each is discussed below.

Choice of Law. There is no general federal common law of contracts. It follows that the validity of a forum selection clause must be determined by reference to state contract law. If the contract containing the clause contains a choice-of-law clause, the court should apply the law of the state named in the clause to determine whether the clause is valid. If the contract containing the clause does not contain a choice-of-law clause, the court should perform a choice-of-law analysis to determine what law to apply to this issue.

General Rules. The court should apply the general rules of contract law to determine whether a clause is valid. If the contract containing the clause fails for lack of consideration, for example, the clause is invalid. Similarly, if a court determines that the clause never became a part of the contract pursuant to a UCC 2-207 analysis, it is invalid.

Special Rules. There are a number of special validity rules that apply exclusively in the context of forum selection clauses. First, a forum selection clause will generally continue to bind the parties to an agreement even after the agreement containing the clause has been terminated or cancelled or repudiated. Second, a party arguing fraudulent inducement must show that the clause itself was induced by fraud. It is generally not enough for the resisting party to show that the contract as a whole was induced by fraud. Third, the traditional rules relating to third-party beneficiaries operate differently when it comes to forum selection clauses. If a non-signatory is so “closely related” to a signatory that it is “foreseeable” that the non-signatory will be bound by the clause, then many courts have held the non-signatory is bound by the clause even if that person does not satisfy the traditional criteria for identifying third-party beneficiaries.

Enforceability

As used herein, the term “enforceability” refers to any special rules that address the question of whether a forum selection clause should be given effect for reasons having nothing to do with whether the clause is valid as a matter of contract law. Many state and federal courts apply a test for enforceability derived from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in The Bremen. This test posits that forum selection clauses are presumptively enforceable but that they may be disregarded if they are (1) unreasonable, or (2) contrary to the public policy of the forum.

Choice of Law. Although federal courts apply state law to issues of interpretation and validity, they generally apply federal law to determine whether a clause is enforceable. This means that most federal courts will apply the test set forth in Bremen – as subsequently refined in Carnival Cruise – to determine whether a forum selection clause is enforceable. The states are not required to follow either of these decisions outside of the admiralty context. Nevertheless, a number of state supreme courts have chosen to adopt the test set forth in The Bremen as a matter of state common law. In these states, there is no meaningful difference between state and federal law on the issue of clause enforceability

In other states, there is a meaningful difference between state and federal law on this issue. Five states have adopted the Model Choice of Forum Act. The test for enforceability under this Act is different than the test set forth in Bremen. In states that have adopted the Act, it is possible that a state court and a federal court may reach different conclusions regarding the enforceability of the same forum selection clause. A number of other state courts have adopted the test laid down in Bremen but reject some or all of the refinements set forth in Carnival Cruise. In these states, it is likewise possible that a state court and a federal court may reach different conclusions regarding the enforceability of the same forum selection clause.

Although state and federal courts may not follow the same test for determining whether a clause is enforceable, there is general agreement among scholars that courts should apply the law of the forum to decide the question. When a contract contains a choice-of-law clause and a forum selection clause, therefore, the court should ignore the choice-of-law clause and apply the law of the forum to resolve the question of whether the clause is enforceable. If a contract does not contain a choice-of-law clause, the court should likewise apply the law of the forum to resolve this issue.

Public Policy – Non-Enforcement Statutes. In Bremen, the Supreme Court held that “[a] contractual choice-of-forum clause should be held unenforceable if enforcement would contravene a strong public policy of the forum in which suit is brought, whether declared by statute or by judicial decision.” U.S. courts look to statutes more frequently than judicial decisions to determine whether a clause is contrary to public policy. These statutes are briefly discussed below.

State Statutes. A forum selection clause will not be enforced if the forum state has enacted a statute directing its courts to ignore it. All fifty states have passed laws stipulating that outbound forum selection clauses should not be enforced under certain circumstances. Illinois has, for example, adopted a law that invalidates clauses that select the courts of another state to resolve disputes relating to building and construction contracts:

A provision contained in or executed in connection with a building and construction contract to be performed in Illinois that . . . requires any litigation, arbitration, or dispute resolution to take place in another state is against public policy. Such a provision is void and unenforceable.

A list of similar statutes in other states can be found here. A discussion of how these statutes operate in practice can be found here. It is important to note that invalidating statutes are not all drafted the same way. These differences in language occasionally give rise to disputes as to whether a given statute applies in a particular case.

When the forum has enacted an invalidating statute, state courts in the forum state will always refuse to enforce any forum selection clause selecting the courts of another state. In most cases—though not always—the federal courts sitting in that state will also give effect to state invalidating statutes.

Federal Statutes. There are no federal statutes that specifically direct the courts not to enforce forum selection clauses. There are, however, a number of federal statutes that contain special venue provisions. A recurring question is whether these special venue provisions render forum selection clauses requiring the suit to be brought elsewhere unenforceable. The federal courts have rendered different answers to this question depending on the federal statute.

With respect to FELA claims, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that a contractual provision that purports to limit the ability of a plaintiff to choose a forum is void as against public policy. With respect to the Carmack Amendment, the lower federal courts have similarly held that the special venue provisions in that Act allow individuals whose household goods have been lost or damaged by moving companies to ignore any forum selection clause.

With respect to the claims arising under Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), by contrast, most courts have held that that statute’s special venue provisions do not invalidate forum selection clauses written into plan documents. Most courts have also held that the venue provisions in the Miller Act do not render clauses in construction contracts unenforceable. The courts have also held that the special venue provisions in the American with Disabilities Act do not preclude the enforcement of forum selection clauses requiring suits arising under that statute to be litigated abroad.

Public Policy – Anti-Waiver Statutes. Courts also sometimes decline to enforce a forum selection clause on public policy grounds when they believe that enforcing the clause will ultimately lead to the waiver of a non-waivable right. Many states have chosen to write “anti-waiver” provisions into statutory schemes that confer a particular set of rights. Anti-waiver statutes provide that the rights conferred by the statutory scheme cannot be waived. If a company were to insist that its customers sign a contract waiving the rights granted by the statute, for example, the anti-waiver statute will operate to void the contractual waiver. If a company were to insist that its customers sign a contract that contained a choice-of-law clause selecting the laws of a state that lacks any equivalent to the statutory scheme, the anti-waiver statute will similarly operate to void the choice-of-law clause.

The logic of these decisions may be extended to forum selection clauses. If the enforcement of a forum selection clause will lead to a case being heard by a court that would enforce a choice-of-law clause selecting the law of a state that lacks any equivalent to the statutory scheme, then the anti-waiver statute will void the forum selection clause because (1) the enforcement of the forum selection clause would lead to the enforcement of the choice-of-law clause, and (2) the enforcement of the choice-of-law clause would lead to the waiver of the right granted by the statutory scheme.

There are many cases where state and federal courts have invoked anti-waiver statutes enacted by state legislatures to justify their refusal to enforce forum selection clauses. Since there are fewer federal statutes that contain anti-waiver provisions, this issue necessarily arises less frequently with respect to federal law. The federal courts have, however, recognized (at least in principle) that the anti-waiver statute in the federal securities laws may operate to bar the enforcement of a forum selection clause selecting a foreign court and foreign laws that are less protective. The same result should arguably obtain when a cruise line attempts to use a foreign choice-of-law clause and a foreign forum selection clause to limit their liability to their passengers under the Athens Convention because federal law prohibits cruise companies from adopting liability caps as a matter of contract law.

Reasonableness. The U.S. Supreme Court held in Bremen that forum selection clauses should not be enforced when the resisting party can show that the clause is “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Although reasonableness is a famously slippery concept, the state and federal courts have over the years developed a reasonably consistent set of criteria for deciding when forum selection clauses may be deemed unreasonable.

First, some courts have held that a forum selection clause is unreasonable when its enforcement will result in duplicative litigation. Second, some courts have held that a clause is unreasonable when the plaintiff cannot secure relief in the chosen forum because there are timeliness or jurisdictional problems in that forum, the claims are too small to be economically pursued in that forum, or it would be dangerous or seriously inconvenient or expensive for the plaintiff to sue in the chosen forum. Third, some courts have held that a clause is unreasonable when the resisting party never received notice of the clause. Fourth, some courts have held that a clause is unreasonable when the chosen forum has no connection to the parties or the transaction. Fifth, some courts have held that a clause is unreasonable when it is fundamentally unfair to the resisting party. Finally, the Supreme Court has suggested that a clause may be unreasonable when two Americans agree to resolve their essentially local dispute in a “remote alien forum.”

Procedural Issues

The procedural mechanism for enforcing a forum selection clause varies from state to state. In some states, the defendant files a motion to dismiss for improper venue. In other states, the defendant files a motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens.

In federal court, the procedural mechanism for enforcing a forum selection clause depends on the identity of the chosen court. In Atlantic Marine v. U.S. District Court, the Supreme Court held that when a forum selection clause selects a state court or a foreign court, a defendant seeking to enforce the clause should move to dismiss on the basis of forum non conveniens. When a clause selects another federal court, a defendant should move to transfer on the basis of 28 U.S.C. 1404(a).

When a federal defendant moves to dismiss or transfer on the basis of a forum selection clause, a federal district court must engage in a two-step analysis. At step one, the court must decide whether the clause is “contractually valid.” To answer this question, the court must first interpret the clause to determine whether it is exclusive and applies to the claims at issue. The court must next confirm that the clause was not obtained by fraud, that it binds the relevant parties, and that it has not been terminated or cancelled. Finally, the court must assess whether the clause is enforceable. If a clause is exclusive, applicable, valid, and enforceable, then it is “contractually valid” for purposes of Atlantic Marine, as discussed at greater length here.

When a clause is contractually valid, the Supreme Court held in Atlantic Marine that the private-interest factors cut decisively in favor of enforcement and that case should be dismissed or transferred to the chosen forum absent “extraordinary circumstances.” When a clause is not contractually valid, then the courts may ignore it and consider the usual public- and private-interest factors to resolve the question under 28 U.S.C. 1404(a) or forum non conveniens.

In the absence of a state or federal statute expressly stating a contrary rule, a forum selection clause can neither deprive a court of subject-matter jurisdiction not confer subject-matter jurisdiction upon a court that lacks it.

Inbound Forum Selection Clauses

The foregoing discussion has assumed that the forum selection clause at issue chose a court that is not the forum. This will not always be the case. When the suit is brought in the court named in the clause, the clause may be invoked by the plaintiff in an attempt to defeat the defendant’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction. A discussion of the issues presented by these “inbound” forum selection can be found here.

Many states use the same test to evaluate the enforceability of inbound and outbound clauses. In these states, the question of whether an inbound clause will be evaluated according to the criteria outlined above in the discussion of outbound clauses. In other states, inbound clauses are evaluated under a different framework. In states that have enacted the Model Choice of Forum Act, for example, the courts apply a distinctive test keyed to inbound clauses. In Florida, the state supreme court has interpreted the state’s long-arm statute to mean that out-of-state defendants must have some connection with the state separate and apart from the forum selection clause before personal jurisdiction may be asserted. In Utah, the courts apply a rational basis test to assess the enforceability of inbound clauses that is different from the test they use to determine whether an outbound clause is enforceable.

A number of states have enacted statutes that direct their courts to enforce inbound forum selection clauses so long as they satisfy certain criteria. The New York legislature, for example, has passed a law which provides that:

[A]ny person may maintain an action or proceeding against a foreign corporation, non-resident, or foreign state where the action or proceeding arises out of or relates to any contract, agreement or undertaking for which a choice of New York law has been made in whole or in part . . . and which (a) is a contract, agreement or undertaking, contingent or otherwise, in consideration of, or relating to any obligation arising out of a transaction covering in the aggregate, not less than one million dollars, and (b) which contains a provision or provisions whereby such foreign corporation or non-resident agrees to submit to the jurisdiction of the courts of this state.

When a state has enacted such a statute, the state and federal courts in that state are obliged to apply it to the exclusion of any common-law test to determine whether an inbound forum selection clause is enforceable. A list of additional statutes in this vein may be found here.

It is important to note that while federal courts apply federal law to determine the enforceability of outbound clauses, these courts apply state law to determine the enforceability of inbound clauses. Rule 4(k)(1)(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides that a federal court may assert personal jurisdiction over an out-of-state defendant to the same extent as a state court of general jurisdiction where the federal court is located. When a forum selection clause is invoked by a plaintiff in an attempt to obtain personal jurisdiction over a defendant, therefore, the Rule directs federal courts to apply state law—not federal law—to determine whether that inbound clause is enforceable. An discussion of this issue may be found here.

It is also important to note that a forum selection clause can provide a basis for the assertion of personal jurisdiction regardless of whether it is exclusive or non-exclusive. The distinction between exclusive and non-exclusive clauses is only relevant when the clause selects a court in a different jurisdiction. When a clause selects the court in the jurisdiction where the suit was filed, the issue of exclusivity is neither here nor there.

Other Issues

Floating Clauses. A “floating” forum selection clause ties the choice of forum to a mutable fact that can change after the contract is made. A comprehensive overview of floating clauses can be found here and here.

Empirical Studies. Are there differences in clause enforcement rates across the states? Across federal circuits? Do state courts enforce these clauses at the same rate as federal courts? An in-depth discussion of how courts apply the law of forum selection clauses in practice can be found here.

Erie. State courts always apply state law to determine whether forum selection clauses are enforceable. Federal courts generally apply federal law to answer this same question. This divergence has the potential to encourage forum shopping and the inequitable administration of the law, both of which constitute problems under the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1938 decision in Erie Railroad Company v. Tompkins. This issue is analyzed here.

Damages. U.S. courts are divided as to whether it is appropriate to award attorneys’ fees as damages when one contracting party ignores an exclusive forum selection clause and sues its counterparty in another court. This issue is explored here and here.