Exhausting Remedies Under the TVPA

June 25, 2024

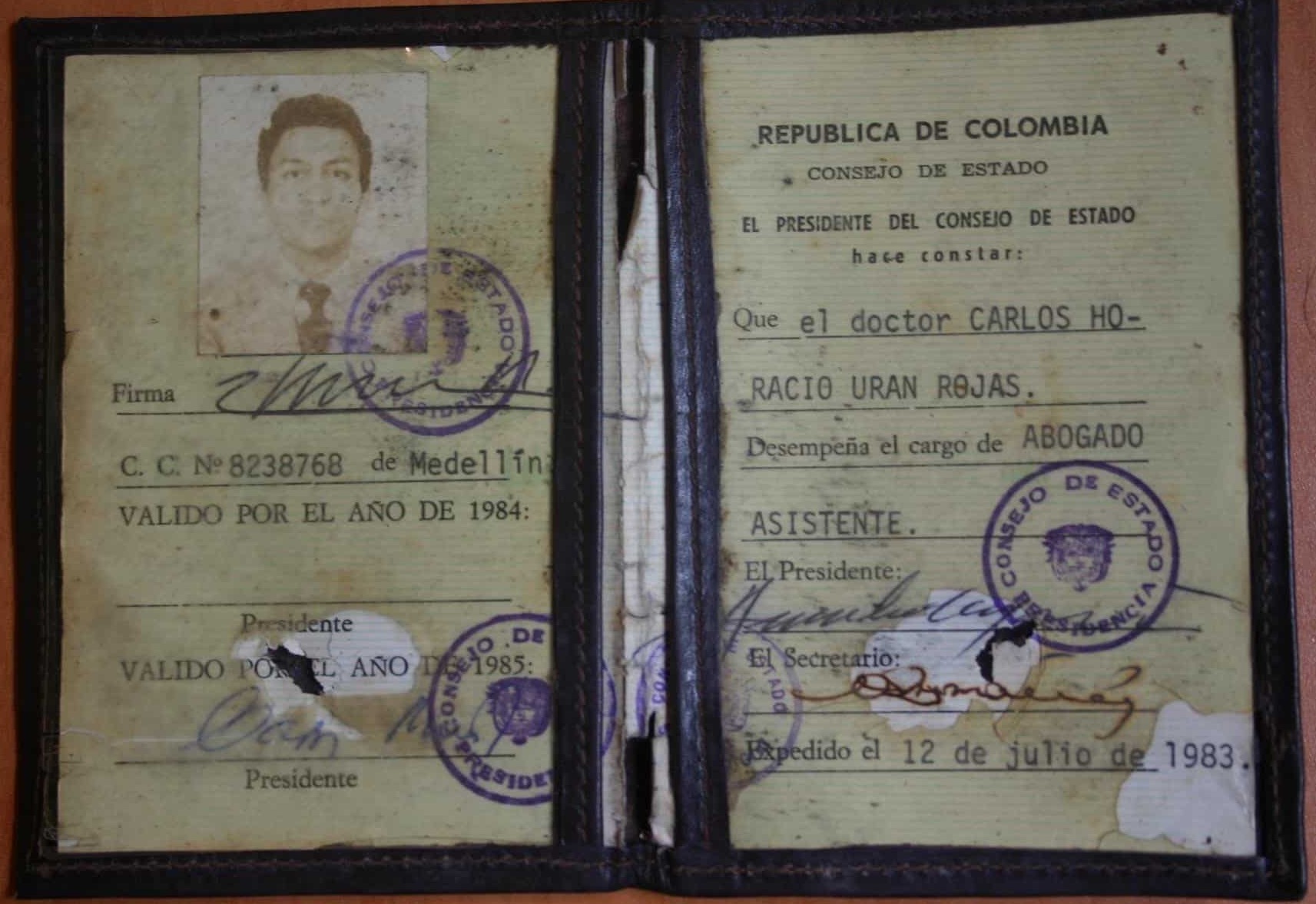

Photo by Helena Urán Bidegain

In 1992, Congress passed the Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA) to create an express cause of action against individuals who, under color of foreign law, commit torture or extrajudicial killing. The TVPA has an exhaustion provision requiring courts to dismiss claims under the provision “if the claimant has not exhausted adequate and available remedies in the place in which the conduct giving rise to the claim occurred.” The TVPA’s legislative history explains that defendants have the burden of proving that plaintiffs failed to exhaust local remedies.

In a recent decision in Bidegain v. Vega, Judge Rodolfo A. Ruiz II (Southern District of Florida) faithfully applied the TVPA’s exhaustion provision, holding that the defendant had not carried his burden to prove that there are adequate and available remedies that the plaintiffs have not exhausted. (Disclosure: I filed an amicus brief supporting plaintiffs.) Using Bidegain as an illustration, this post explores how exhaustion operates under the TVPA. At the end, I suggest that this exhaustion requirement may be more trouble than it’s worth.

Bidegain v. Vega

In 1985, members of the guerilla group M-19 stormed the Palace of Justice in Bogota, Colombia, taking hundreds of hostages. The military assault to retake the Palace left nearly one hundred civilians dead, including the plaintiffs’ father Magistrate Carlos Horacio Urán Rojas. In 1987, the plaintiffs’ mother filed an administrative complaint for herself and her daughters under Article 90 of the Colombian Constitution. In 1995, the family was awarded $187,901.

In 2007, further investigation revealed that Magistrate Urán had left the Palace of Justice alive and was taken to the Colombian Army’s 13th Brigade Cavalry School, commanded by the defendant, Lieutenant Colonel Luis Alfonso Plazas Vega. The Prosecutor General opened criminal investigations, one of which two of the plaintiffs and their mother joined as civil parties. Despite their urgings, Vega was not named in the investigation.

In 2014, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) found the Colombian government liable for the torture and murder of Magistrate Urán, ordering the government to pay compensation and to investigate and prosecute those responsible. But the investigation has made little progress and remains ongoing a decade after the IACHR’s judgment and nearly two decades after it was opened.

The defendant Vega moved to the United States in 2016. In 2022, the plaintiffs sued Vega under the TVPA for the torture and murder of their father. Vega moved for summary judgment arguing that plaintiffs failed to exhaust four adequate and available remedies under Colombian law: (1) a civil action under the Colombian civil code; (2) an action under Article 90 of the Colombian Constitution; (3) a victim-initiated expansion of the ongoing criminal investigation; and (4) civil reparations through the criminal proceeding.

The TVPA’s Exhaustion Requirement

When Congress created express causes of action for torture and extrajudicial killing in the TVPA, it also provided that “[a] court shall decline to hear a claim under this section if the claimant has not exhausted adequate and available remedies in the place in which the conduct giving rise to the claim occurred.” The Senate Report on the TVPA explains that exhaustion was intended to be “an affirmative defense.”

Once the defendant makes a showing of remedies abroad which have not been exhausted, the burden shifts to the plaintiff to rebut by showing that the local remedies were ineffective, unobtainable, unduly prolonged, inadequate, or obviously futile. The ultimate burden of proof and persuasion on the issue of exhaustion of remedies, however, lies with the defendant.

Congress expected that this exhaustion defense would rarely succeed. Because perpetrators usually keep their assets in their home countries and because it is generally easier to establish personal jurisdiction there, the Senate Report predicted that victims would sue in the United States “only as a last result.” “Therefore, as a general matter,” the Report continued, “the committee recognizes that in most instances the initiation of litigation under this legislation will be virtually prima facie evidence that the claimant has exhausted his or her remedies in the jurisdiction in which the torture occurred.”

Relying on this legislative history, the Eleventh Circuit has described a defendant’s burden as “substantial” and cautioned that “doubts concerning the TVPA and exhaustion” must be “resolved in favor of the plaintiffs.”

Only Adequate and Available Remedies Must Be Exhausted

The TVPA’s text requires exhaustion only of “adequate and available remedies” where the torture or extrajudicial killing occurred. The Senate Report elaborates, stating that plaintiffs may rebut an exhaustion argument “by showing that the local remedies were ineffective, unobtainable, unduly prolonged, inadequate, or obviously futile.” Note the word “or,” indicating that this list is disjunctive.

In Bidegain, Judge Ruiz found that filing a civil action under Colombia’s civil code was not an available remedy. Under Colombian law, as civil parties to a criminal proceeding, the plaintiffs were required to renounce their rights to filed independent civil claims tied to the same facts under investigation. Additionally, the statute of limitations for a civil claim under Colombian law would have run in 2017 at the latest, ten years after discovery of the new evidence concerning Magistrate Urán’s death.

Judge Ruiz reached the same conclusion with respect to expansion of the criminal investigation and reparations in the criminal proceeding. As to the first, he noted that plaintiffs appeared to have almost no influence over the investigation. As to the second, he concluded that “continued delays in resolving the criminal proceeding” made restitution “unavailable and inadequate.”

The district court’s conclusions in Bidegain are consistent with the decisions of other courts interpreting the TVPA’s exhaustion requirement. Another district court in Florida has held that the running of a statute of limitations makes a remedy unavailable. And district courts in Florida and Massachusetts have held that delays in resolving criminal cases can make civil remedies unavailable.

Only Remedies Against the Defendant Must Be Exhausted

Judge Ruiz rejected the defendant’s argument concerning Article 90 of the Colombian Constitution for two different reasons. The first was that it provides remedies against the Colombian government, not against the alleged perpetrator.

“The TVPA, by its plain language, provides recourse against individuals, not foreign governments,” Judge Ruiz noted, “and a remedy against Colombia thus falls outside the scope of the statute’s exhaustion requirement.” This conclusion is consistent with the TVPA’s legislative history. The Senate Report’s discussion of the exhaustion requirement refers consistently to “the alleged torturer” and makes no mention of remedies that might be available against foreign governments.

Successful Exhaustion Does Not Bar Claims Under the TVPA

The second reason for rejecting the defendant’s argument with respect to Article 90 was that the plaintiffs had in fact exhausted this remedy. Plaintiffs’ mother filed an Article 90 claim in 1987, and the family was awarded damages. The Eleventh Circuit has held that success in exhausting remedies does not bar claims under the TVPA.

This conclusion is again supported by the TVPA’s legislative history. The Senate Report states: “A court may decline to exercise the TVPA’s grant of jurisdiction only if it appears that adequate and available remedies can be assured where the conduct complained of occurred, and that the plaintiff has not exhausted local remedies there” (emphasis added). If a plaintiff has exhausted local remedies, the second requirement is not met, and a court may not decline to hear the case.

Second Thoughts About Exhaustion

Judge Ruiz’s decision in Bidegain provides a good example of applying the TVPA’s exhaustion requirement as Congress intended. But it is not clear to me that Congress should have put him (and the parties) to the trouble.

Under customary international law, exhaustion of local remedies is required before filing a claim in an international tribunal. But customary international law does not require such exhaustion before filing a claim in domestic court. The relationships among domestic courts are governed by domestic law doctrines such as forum non conveniens and lis pendens.

The House Report suggests two reasons for the TVPA’s exhaustion requirement: (1) respect for foreign legal systems, and (2) avoiding “unnecessary burdens” on U.S. courts. But it is not clear that the TVPA’s exhaustion requirement delivers either. Judge Ruiz thought that requiring an exhaustion inquiry showed disrespect to Colombia by requiring him to “police the legal and political practices of another country.”

As for “unnecessary burdens,” it seems that the exhaustion requirement itself creates these. In Bidegain, the arguments over exhaustion required several rounds of briefing and submission of expert testimony by both sides. These arguments delayed the proceedings for more than a year. Yet Congress expected that exhaustion arguments would rarely succeed. “[I]n most instances,” the Senate Report states, “the initiation of litigation under this legislation will be virtually prima facie evidence that the claimant has exhausted his or her remedies in the jurisdiction in which the torture occurred.” What, then, is to be gained by spending months or years litigating a question in which the result is virtually foreordained?

Conclusion

Bidegain v. Vega is a good example of how exhaustion analysis should be done under the TVPA. But the question remains whether it is worth doing at all.