The Impossibility of Schrödinger Service

May 7, 2025

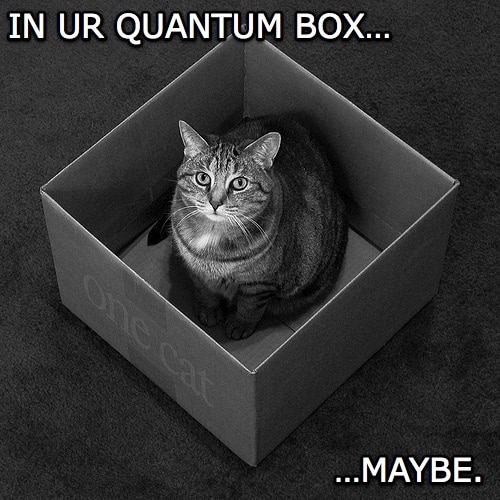

In quantum physics, a system can exist in two states at the same time. When the system is observed, it settles into one of those states. The physicist Erwin Schrödinger found this notion somewhat absurd. In a thought experiment, he imagined a cat in a closed box with a flask of poison and a radioactive atom. If the atom decayed, the flask would break, and the cat would die. If the atom did not decay, the flask would not break, and the cat would live. The theory that the atom could exist in two states simultaneously meant that the cat was both dead and alive at the same time.

What Does This Have to Do with Service of Process?

In a prior post, I discussed the decision in Zobay v. MTN Group Ltd. by Judge Carol Bagley Amon (Eastern District of New York) to allow plaintiffs to serve process on foreign defendants through their U.S. counsel. The magistrate judge had authorized such service under Rule 4(f), which covers service in a foreign country. Judge Amon instead held that such service was authorized under Rule 4(e), which governs service in the United States.

Relying on Rule 4(e) allowed Judge Amon to avoid the Hague Service Convention, which applies when “there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.” The Convention is exclusive, which means that only the means of service listed in the Convention are permitted. Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(f)(3), a court has broad discretion to order service by means consistent with due process—but only if such means are “not prohibited by international agreement.” Because service through counsel is not among the Convention’s listed means, such service is prohibited by international agreement and therefore cannot be ordered under Rule 4(f)(3).

Rule 4(e) comes with its own limitations, however. First, the means of service must be authorized by state law. Second, service must be completed within the United States so that the Convention does not apply. These limitations apply not just to service through U.S. counsel but also to other means of serving foreign corporations in the United States, such as service on a corporate affiliate or state secretary of state, both of which I have discussed here.

Friend-of-TLB and leading service-of-process expert Ted Folkman doesn’t like the limitations that come with Rule 4(e), at least when it comes to service through counsel. At Letters Blogatory, he responded to my post on Zobay by suggesting a kind of “Schrödinger service.” Service may be permissible under Rule 4(f)(3), he wrote, “because the lawyer is going to inform the defendant of the important facts” about the case while the defendant is outside the United States. At the same time, the Hague Service Convention does not apply because “service is complete on delivery of the summons to the lawyer,” which means that there is no occasion to transmit documents for service abroad. In other words, service occurs outside the United States for purposes of Rule 4(f)(3) and inside the United States for purposes of the Convention. Problem solved!

The Cat Is Either Dead or Alive

Just as Erwin Schrödinger doubted that a cat could be both alive and dead at the same time, I doubt that service of process can occur outside the United States and inside the United States at the same time.

Both Rule 4 and the Hague Service Convention are written in binary terms. Rule 4(e) covers service “in a judicial district of the United States,” whereas Rule 4(f) covers service “at a place not within any judicial district of the United States.” Rules 4(e) and 4(f) are mutually exclusive—it is impossible to be “in a judicial district of the United States” and “not within any judicial district of the United States” at the same time.

By the same token, the Hague Service Convention applies when “there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.” Again, this is binary. There either is occasion to transmit a document for service abroad, or there is not.

Of course, the critical question is not whether Rule 4 and the Convention are binary but whether the two halves of each are congruent. More specifically, is “not within any judicial district of the United States” under Rule 4 the same as “abroad” under the Convention? I think the answer is yes. If service is being made “at a place not within any judicial district of the United States,” then it is necessarily being made “abroad” for purposes of the Convention.

Writing about this same question three years ago, Ted said this:

Perhaps there is some kind of “spooky action at a distance” that allows a court to say that the document does not need to be transmitted abroad for service, but that the service is effected abroad? Perhaps the delivery of the document here effects service there? This seems the most promising practical approach, but I haven’t seen any court do it convincingly so far.

I suggest that we haven’t seen any court do it convincingly so far because it is impossible to do. Just as Schröedinger’s cat is either dead or alive, service must occur either here or there.