New Bill Would Amend the Alien Tort Statute to Apply Extraterritorially

May 9, 2022

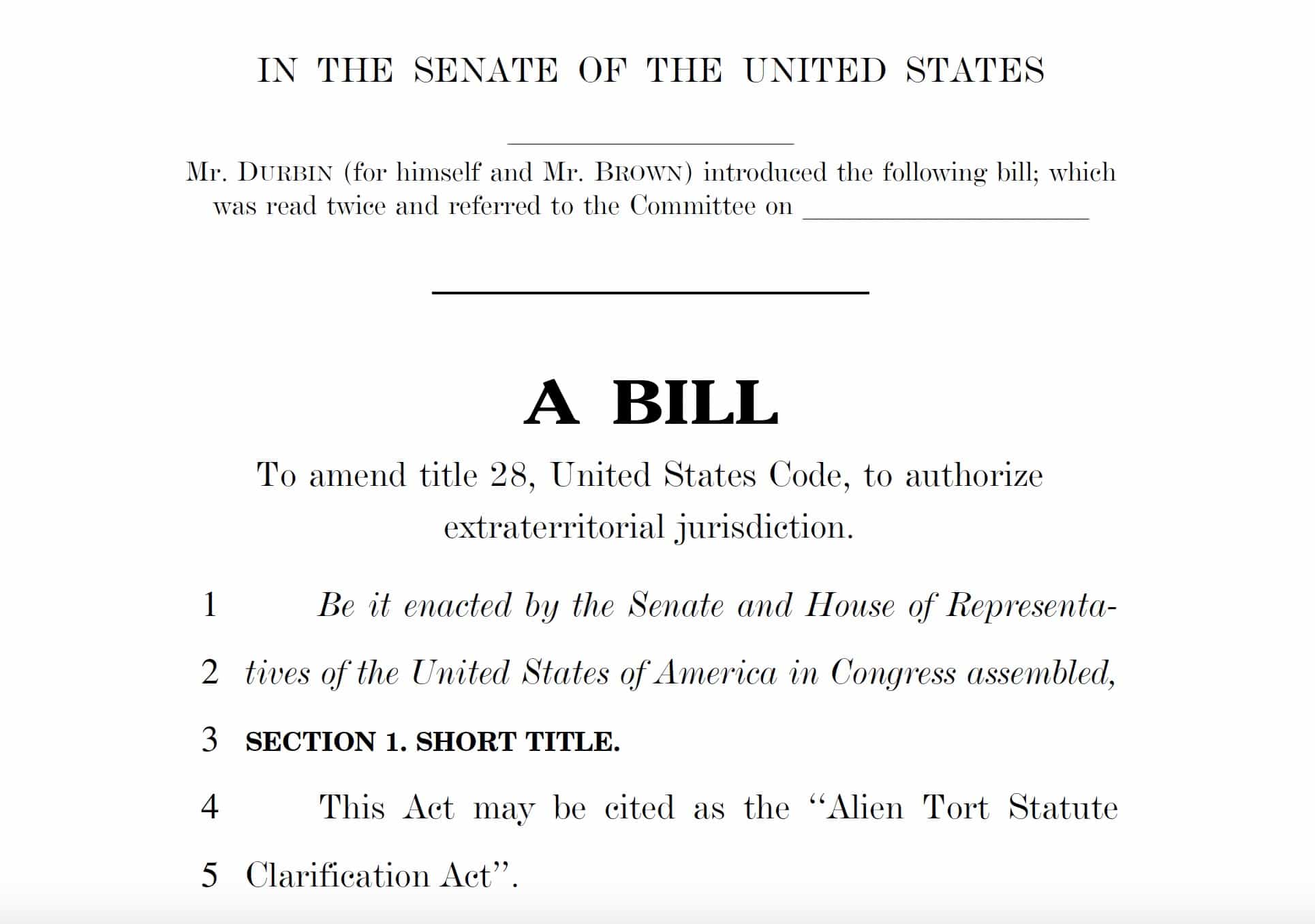

Last week, Senators Dick Durbin and Sherrod Brown introduced a new bill, the Alien Tort Statute Clarification Act (ATSCA), that would amend the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) to apply extraterritorially. Since 1980, plaintiffs have relied on the ATS to bring international human rights claims in federal court against individuals and corporations. But since 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly narrowed the cause of action under the ATS by applying the presumption against extraterritoriality. The ATSCA seeks to overturn those decisions and restore the ATS’s application to human rights violations abroad.

The Narrowing of the ATS Cause of Action

The ATS was part of the First Judiciary Act of 1789. As currently codified, it provides: “The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” The ATS lay largely dormant until 1980, when the Second Circuit held in Filartiga v. Pena-Irala that it permitted Paraguayan citizens whose relative was tortured to death by a police inspector in Paraguay to bring claims against the inspector in U.S. federal court. The defendant was present in the United States and was personally served in New York. Under the plain language of the ATS, the plaintiffs were aliens, torture is a tort, and torture by a state actor violates customary international law, the modern equivalent of “the law of nations.”

In 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court in effect affirmed Filartiga by recognizing an implied cause of action for human rights claims under the ATS in Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain. The Court limited the cause of action, which it created as a matter of federal common law, to violations of international human rights norms that are as well established as the violations that Congress had in mind in 1789 (like piracy and infringement of the rights of ambassadors). This limitation soon raised the question whether claims against corporations met the Sosa standard. The Second Circuit held that they did not, reasoning in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum (2010) that there was no well-established norm of corporate liability in customary international law.

The Supreme Court granted cert to resolve the corporate liability question but, after additional briefing, decided the case on a different ground. In Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum (2013), the Court applied the presumption against extraterritoriality to the ATS cause of action. It concluded that claims by aliens against a non-U.S. corporation for human rights violations that occurred abroad did not “touch and concern” the United States sufficiently to rebut the presumption.

The Court tried again to resolve the corporate liability question in Jesner v. Arab Bank (2018). But it fractured badly and could agree only that the ATS cause of action should not apply to foreign corporations.

In Nestle USA v. Doe (2021), the Court took up corporate liability under the ATS for the third time. Five Justices agreed that there was no reason to distinguish between corporations and natural persons as defendants, although they did so in separate opinions. But ultimately the Court decided the case on extraterritoriality grounds. Abandoning Kiobel’s “touch and concern” test, the Court instead applied its new presumption against extraterritoriality, which uses a two-step framework that looks first for a clear indication of extraterritoriality and second to see if applying U.S. law would be domestic based on the “focus” of the provision. Although the parties disagreed about the focus of the ATS, the Court found it unnecessary to resolve that question because the plaintiffs had not alleged sufficient conduct in the United States relevant to any possible focus.

Although the Supreme Court had referred to the need for conduct in the United States relevant to a provision’s focus before, the Court had never actually applied such a requirement until Nestle. As I noted at the time, Nestle’s requirement of conduct in the United States seems to put an end to ATS suits against individuals. In cases like Filartiga, all the conduct occurs abroad, and the only connection to the United States is that the defendant has moved here, temporarily or permanently, and is subject to personal jurisdiction.

Congress has created other causes of action that plaintiffs can use to bring some human rights claims, but these are more limited than the ATS. The Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA) creates an express cause of action for torture and extrajudicial killing under color of foreign law, but it applies only to suits against individuals and not to suits against corporations. The Trafficking Victim Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) does apply to corporations, but it is limited to claims of forced labor, slavery, human trafficking, and the like.

The Alien Tort Statute Clarification Act

The ATSCA would amend the ATS to apply extraterritorially by adding a new subsection (b) to the existing provision:

(b) EXTRATERRITORIAL JURISDICTION.—In addition to any domestic or extraterritorial jurisdiction otherwise provided by law, the district courts of the United States have extraterritorial jurisdiction over any tort described in subsection (a) if—

(1) an alleged defendant is a national of the United States or an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence (as those terms are defined in section 101 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101)); or

(2) an alleged defendant is present in the United States, irrespective of the nationality of the alleged defendant.

This language is borrowed directly from the TVPRA’s provision on extraterritoriality (18 U.S.C. § 1596(a)), a statute that has enjoyed broad bipartisan support in Congress. Adding this new language to the ATS would provide a clear indication of extraterritoriality sufficient to rebut the presumption at step one of the Supreme Court’s two-step framework, thus overturning its decisions limiting the geographic scope of the ATS.

Under the new language, the ATS would apply to U.S. corporations because they are “national[s] of the United States.” The ATS would also apply to foreign corporations if they are “present in the United States.” One recent decision interpreting the TVPRA has suggested that “present in” might require physical presence in the United States. But the ATSCA’s findings indicate that the ATS should reach to the limits of personal jurisdiction. Finding (8) says: “The Alien Tort Statute should be available against those responsible for human rights abuses whenever they are subject to personal jurisdiction in the United States, regardless of where the abuse occurred.” Of course, under Daimler AG v. Bauman (2014), it is often hard to establish personal jurisdiction over foreign corporations when the claims arise abroad. But when personal jurisdiction exists, the ATSCA would extend the ATS to foreign corporations as well.

The ATSCA’s findings specifically indicate a desire to hold corporations responsible for human rights violations abroad, buttressing the conclusion that five of the Justices have already reached. Finding (4) states that “[w]hen corporations commit or aid and abet human rights violations directly and through their supply chains, they should be held accountable.” As Finding (5) goes on to explain, “[i]mpunity for corporations who violate human rights unfairly disadvantages businesses that respect and uphold human rights. Companies that respect human rights should have a level playing field with companies that do not, such as those that would continue to do business in areas of the world known for mass atrocities or war crimes, including the Xinjiang region of the People’s Republic of China or in the Russian Federation amidst the ongoing invasion of Ukraine.”

Importantly, the ATSCA would also restore ATS jurisdiction over claims against individuals for human rights violations abroad, like the Filartiga case. As Finding (3) notes, “[h]uman rights abusers continue to seek refuge in the United States, including foreign government and military officials and leaders of death squads and other violent groups.” Abusers who come to the United States are subject to personal jurisdiction here, based either on residence or on personal service, and would be “present in” the United States for purposes of the amended ATS.

Moreover, Nestle’s requirement of conduct in the United States would no longer apply to suits against corporations or individuals. Nestle adopted that limitation on the ATS cause of action under the second, “focus” step of the presumption against extraterritoriality analysis. But the Court has made clear that when “there is a clear indication at step one” a court “do[es] not proceed to the ‘focus’ step.” If the ATSCA is enacted, it would provide such a clear indication, eliminating Nestle’s limitation.

Prospects for Passage

It is hard to say what the prospects for passage of the ATSCA are. Its jurisdictional language is certainly not radical. It repeats almost word for word the language of the TVPRA, which Congress has already reauthorized several times.

Opposition can be expected from some U.S. business groups. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and others have in the past argued against the extraterritorial application of the ATS. On the other hand, a number of small and mid-sized chocolate companies filed an amicus brief supporting the plaintiffs in Nestle, complaining of the uneven playing field that the ATSCA aims to level. Moreover, the invasion of Ukraine has made businesses newly aware of possible complicity in supporting violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. The billions of dollars that companies are losing as they cut ties with Russia dwarfs the costs of addressing human rights violations elsewhere.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that the ATSCA would restore the ATS as a tool against individual human rights abusers who come to the United States. Such individuals had been liable to suit under the ATS since Filartiga, but the Supreme Court’s addition in Nestle of a requirement of conduct in the United States effectively put an end to such suits. Individuals may still be sued under the TVPA, but only for torture and extrajudicial killing. A Russian officer who commits war crimes in Ukraine, for example, could not held civilly liable if he came to the United States. It is hard to think of a member of Congress who want to shield such defendants from liability.