Potential Impact of Recent Cartel Designations

July 23, 2025

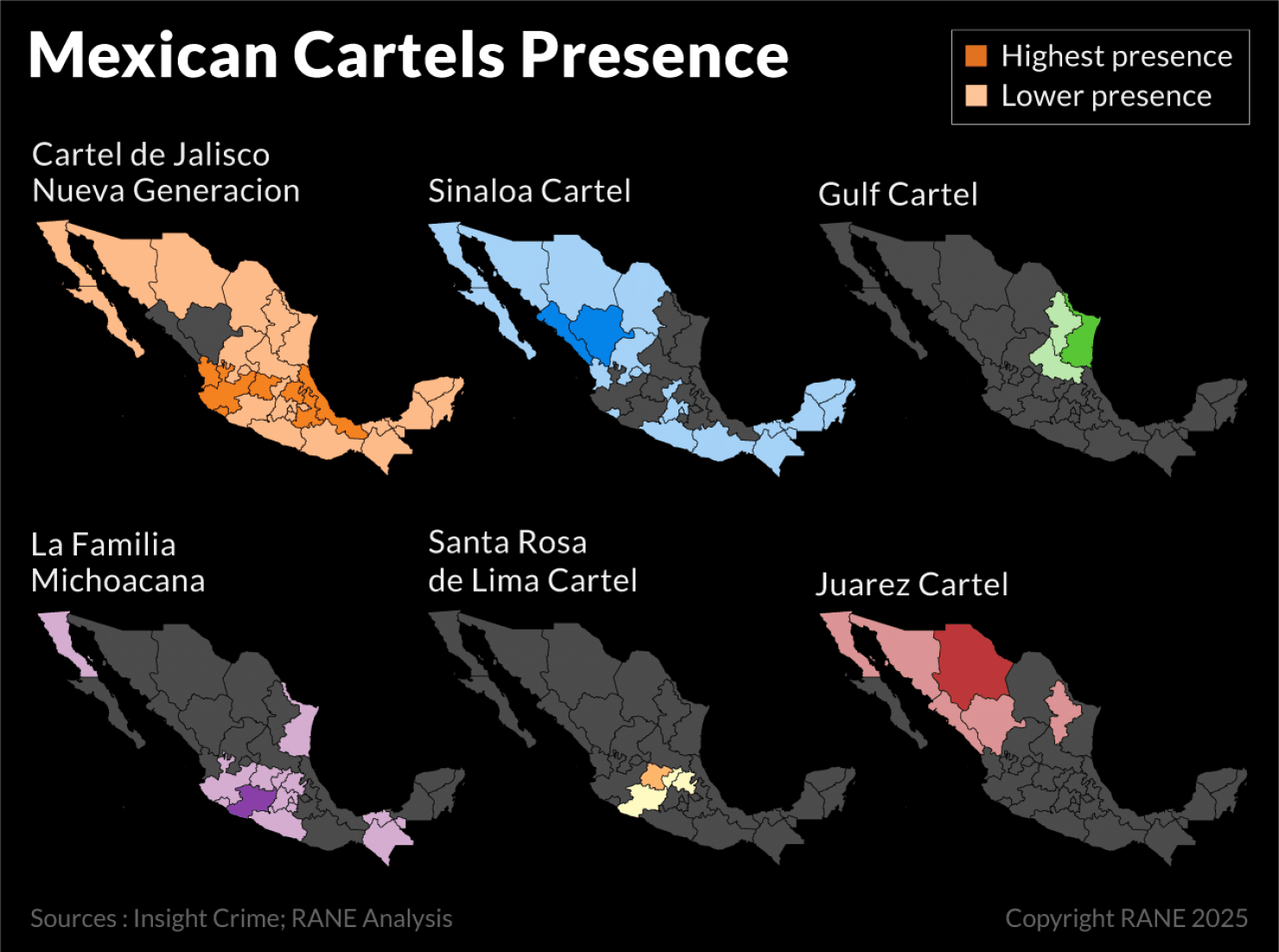

On January 20, 2025, President Trump issued Executive Order (E.O.) 14157, directing the Secretary of State to designate international criminal organizations, including drug cartels, as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). On February 20, 2025, the Secretary of State designated the following cartels under both statutes: Tren de Aragua, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Cártel de Sinaloa, Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, Cártel del Noreste (formerly Los Zetas), La Nueva Familia Michoacana, Cártel de Golfo (Gulf Cartel), and Cárteles Unidos.

This post explores the potential effect of these designations on civil litigation in the United States.

The Anti-Terrorism Act

The Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) provides a cause of action for a U.S. national “injured in his or her person, property, or business by reason of an act of international terrorism” to sue for treble damages (and attorney’s fees and costs). Claims may be brought under this part of the ATA against defendants who are not designated as FTOs, but they face significant hurdles. For example, in Zapata v. HSBC Holding, PLC. (EDNY 2019) victims who suffered attacks by five of Mexico’s most notorious drug cartels sued U.S., British, and Mexican banks that allegedly laundered the proceeds from the cartels’ drug deals. The ATA claims were dismissed against one defendant for lack of personal jurisdiction. As to the others, the complaint failed to adequately allege both that the money laundering by the banks met the statutory definition of “international terrorism” and that the money laundering caused the plaintiffs’ injuries. The District Court noted that:

The ATA does not provide for secondary liability unless the act of international terrorism in question was carried out by an entity formally designated as a foreign terrorist organization (see id. § 2333(d)(2)), which is not true of the Cartels. [citation omitted.] Accordingly, for Plaintiffs’ complaint to survive, it must plausibly allege not that the attacks that injured Plaintiffs were acts of international terrorism, but that HSBC’s money-laundering activities were, in and of themselves, acts of international terrorism that proximately caused Plaintiffs’ injuries.

The drug cartels that allegedly harmed the plaintiffs in the Zapata case included the Sinaloa Cartel, the Los Zetas Cartel and the Gulf Cartel—all of which have since been designated as foreign terrorist organizations.

Secondary Liability under the ATA

As amended by the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) at 18 U.S.C. § 2333(d)(2), the ATA provides that “liability may be asserted as to any person who aids and abets, by knowingly providing substantial assistance, or who conspires with the person who committed” an act of international terrorism, so long as that person has been designated as a “foreign terrorist organization.” This is known as secondary liability. As the statutory language suggests and as the Supreme Court emphasized in Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh (2023), the entity that actually “committed, planned, or authorized” the relevant act of international terrorism must be so designated in order for a secondary liability claim to be brought against those who aided and abetted them.

The drug cartel designations thus open the door for secondary liability lawsuits against banks and others that may have aided (or conspired with) the cartels. In litigation like the Zapata case, plaintiffs will not need to show that the bank itself committed an act of terrorism that caused the injuries, but instead only that the bank knowingly provided “substantial assistance” to (or conspired with) the drug cartel that committed the act of terrorism that inflicted damages on the plaintiff. Although the secondary liability standard is significantly easier to meet (the assistance to the drug cartel need not be direct), it still requires adequate allegations of knowledge. In particular, courts have held that the defendant must be at least “generally aware of his role as part of an overall illegal or tortious activity at the time that he provides the assistance,” a standard that can be difficult—but not impossible—to meet with respect to banks that provide financial services to terrorist organizations.

Although banks are easy to locate and often have deep pockets and attachable assets, secondary liability claims may, of course, be brought against individuals and other entities as well. A recently filed lawsuit claims, for example, that Tareck El Aissami, a Venezuelan government official, worked to establish a “violent paramilitary organization” involved in the drug trade, which came to be known as “El Tren de Aragua” (“TdA”), one of the recently designated cartels. Although that suit is based on the conduct of a different designated entity—the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (“FARC”)—it highlights that individuals who aid and abet TdA and other designated cartels now risk liability in the United States under the ATA. This assumes, of course, that courts here have personal jurisdiction over them. The Supreme Court recently held in Fuld v. PLO (2025) that Congress may authorize federal courts to exercise personal jurisdiction under the ATA that state courts could not. As currently written, the ATA – unlike the statute in Fuld – does not currently say anything explicit about personal jurisdiction, but the effect of Fuld might arguably be to expand personal jurisdiction of federal courts under Rule 4(k)(2) in cases brought under a federal statute, especially those statutes like the ATA that relate to terrorism and national security.

Finally, it bears mention that a February 2025 memorandum from Attorney General Pam Bondi set out several concrete measures designed to ramp up criminal prosecutions related to drug cartel activity. Criminal investigations and prosecutions sometime provide evidence that is useful to plaintiffs in civil litigation involving the same parties—another reason to expect more ATA cases involving drug cartels.

Financial Implications

The cartels’ designations as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) also have important legal effects, distinct from those that follow from the FTO designations. An SDGT designation triggers primarily financial sanctions managed by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). In a March 2025 alert, OFAC explained the impact of the cartel designations. The office indicated explained that while most were already sanctioned (with Cárteles Unidos as the lone outlier) under other authorities, such as the Kingpin Act, E.O. 14059, and/or E.O. 13581, the SDGT designations of the cartels extend secondary sanctions risks to foreign financial institutions that “knowingly conducted or facilitated any significant transaction on behalf of any person whose property and interests in property are blocked.” Foreign financial institutions now risk being cut off from the U.S. financial system via correspondent or payable-through account sanctions should they engage in conduct prohibited by secondary sanctions. As for the cartels themselves, these designations mean that all of their property (and interests in property) in the United States or in the possession or control of U.S. persons are blocked.

Conclusion

Although we have so far seen little civil litigation following from the cartel designations, it has only been a few months since they took effect. To recover on a secondary liability claim alleging support to one of these cartels, plaintiffs must, among other things, show that the cartel committed, planned, or authorized an act of international terrorism after the date of designation, which was February 20, 2025. But the large amounts of money involved in the transnational drug trade, as well as the renewed focus on criminal prosecutions of the drug cartels under President Trump, both point towards more ATA litigation involving Latin American defendants and drug-related violence in the years to come.