Revising Forum Non Conveniens Through § 1404?

December 10, 2024

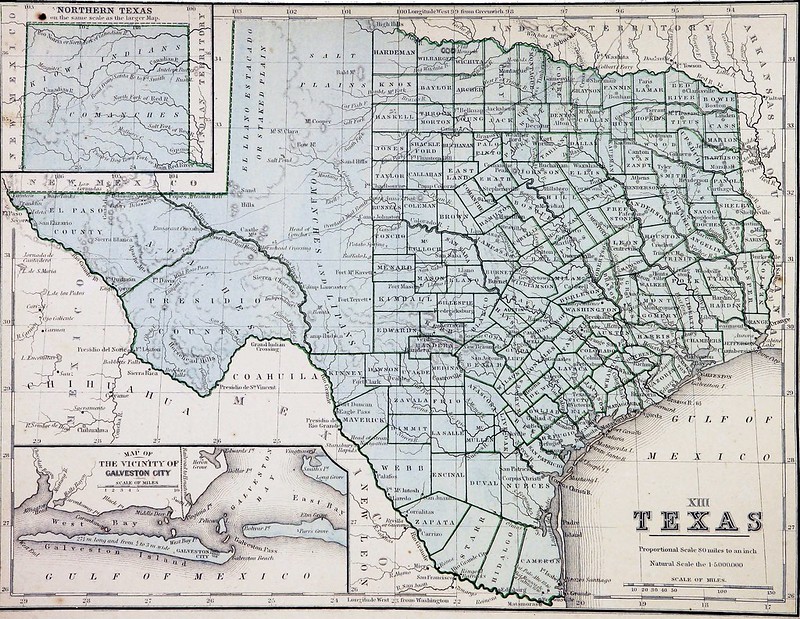

“Texas” by Stuart Rankin (CC BY-NC 2.0)

I have written more than anyone probably should about forum non conveniens (FNC), but much of it boils down to some commonsense updating of the Gulf Oil factors: acknowledge the effects of changing technology, particularly on travel; require defendants to be specific about their evidentiary burdens; don’t overweight choice-of-law difficulties or docket congestion; don’t second guess plaintiffs’ willingness to undertake some inconvenience of their own; and don’t discount plaintiffs’ choice of an otherwise permissible forum just because they are not locals themselves.

But old habits die hard, and I haven’t been holding my breath. Imagine, then, my surprise to find many of these reforms embraced in a series of recent opinions by the Fifth Circuit. The catch—and it is an interesting one—is that these updates have been made not in the context of FNC, but for discretionary transfers under 28 U.S.C. § 1404. The § 1404 analysis also relies on the Gulf Oil factors, though it is supposed to be easier to secure a § 1404 transfer to another federal court than an outright dismissal for FNC.

The effect of the recent developments in the Fifth Circuit, however, is to make it much easier to get a case dismissed outright for FNC (on the vague idea that the case might be refiled in a foreign court) than it is to get a case transferred to another federal district (which is theoretically just a change in location, not a change in the applicable law or procedural rules). And that result seems backwards.

Section 1404 and Forum Non Conveniens

As a refresher, transfers under § 1404 and dismissals for FNC have always been linked. The Supreme Court first approved the use of FNC by federal courts outside the context of admiralty in Gulf Oil Co. v. Gilbert (1947). Gulf Oil directed federal courts to weigh private and public interests to decide whether to dismiss a case. In the words of Justice Jackson, the private interests include:

- the relative ease of access to sources of proof;

- availability of compulsory process for attendance of unwilling, and the cost of obtaining attendance of willing, witnesses;

- possibility of view of premises, if view would be appropriate to the action; and

- all other practical problems that make trial of a case easy, expeditious and inexpensive.

- (There may also be questions as to the enforceability of a judgment if one is obtained.)

In describing the relevant public interests, Justice Jackson explained:

- Administrative difficulties follow for courts when litigation is piled up in congested centers instead of being handled at its origin.

- Jury duty is a burden that ought not to be imposed upon the people of a community which has no relation to the litigation. In cases which touch the affairs of many persons, there is reason for holding the trial in their view and reach rather than in remote parts of the country where they can learn of it by report only. There is a local interest in having localized controversies decided at home.

- There is an appropriateness, too, in having the trial of a diversity case in a forum that is at home with the state law that must govern the case, rather than having a court in some other forum untangle problems in conflict of laws, and in law foreign to itself.

In Gulf Oil, the Supreme Court approved dismissal of a case filed in one federal court because the district court thought it was more appropriately heard in another federal court. Congress quickly stepped in with 28 U.S.C. § 1404, which enabled federal judges to simply transfer cases between districts in such situations. In its current form, the key provision of § 1404 reads in full:

For the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice, a district court may transfer any civil action to any other district or division where it might have been brought or to any district or division to which all parties have consented.

The Reviser’s Notes explains that this new provision “was drafted in accordance with the doctrine of forum non conveniens.” But because transfer is a much less harsh outcome than outright dismissal, the Supreme Court explained in Norwood v. Kirkpatrick (1955) that § 1404 is “intended to permit courts to grant transfers upon a lesser showing of inconvenience” than that required for FNC. “This is not to say that the relevant factors have changed” from Gulf Oil, the Court explained, “but only that the discretion to be exercised is broader.”

Expanding Forum Non Conveniens

After the adoption of § 1404, FNC was used primarily to dismiss cases in favor of courts outside the United States. Traditionally (as I’ve documented with others), FNC was reserved for cases in which neither the plaintiffs nor the defendants were local to the forum. But by the 1980s, FNC was being used routinely to dismiss cases brought by foreign plaintiffs against local defendants. The Supreme Court’s decision in Piper Aircraft Co. v. Reyno (1981) made such dismissals easier by discounting the plaintiff’s forum choice when the plaintiff was suing away from home.

Meanwhile, the Gulf Oil factors devolved to simple rules of thumb that typically pointed in favor of the defendant’s motion to dismiss. All a defendant has to do, many courts have suggested, is invoke the possibility of some evidence or witnesses located abroad to establish the inconvenience of litigating in the plaintiff’s chosen forum (even if that forum is the defendant’s home base). Any case involving parties from different countries will likely involve choice-of-law questions and possibly the application of foreign law. Foreign evidence and witnesses might require translation. And Piper invited questioning of plaintiffs’ motives for filing any case outside their home courts. “Forum shopping” in this context is an entirely bad word.

Narrowing § 1404

In walks the Fifth Circuit, ready to make forum shopping great again. Just in the last few years, the Fifth Circuit has repeatedly used writs of mandamus to stop (or try to reverse) the transfer of high-profile public law cases to district courts in other circuits. Traditionally, transfer decisions have been largely shielded from appellate review. To explain why these recent transfer decisions reflect such manifest abuses of discretion as to warrant mandamus, then, the Fifth Circuit has embraced a significantly more limited view of § 1404.

For example, in a case about 3D printer designs for ghost guns, Judge Edith Jones explained that the district court erred by not requiring the defendant (the New Jersey Attorney General) to explain with specificity what evidence was in New Jersey, including which witnesses might be beyond the compulsion of a district court in Texas. Nor is transfer warranted, she explained, simply because a Texas court might have to apply the law of another state (like New Jersey)—that’s just part of what the federal courts do. The district court simply did not give enough weight to the plaintiff’s initial choice of forum.

In a more recent decision in a challenge to the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Fifth Circuit similarly emphasized that the plaintiffs’ choice of forum should generally be respected: district courts should ignore arguments that the chosen forum inconveniences the plaintiffs (that’s for the plaintiffs to decide), and defendants should also expect some inconvenience when being sued. In particular, courts should reject arguments about the location of the parties’ lawyers, especially given the ease of modern travel. (Notably, Judge Don Willett acknowledged that this clarification about counsels’ convenience differed from the circuit’s FNC caselaw, which does permit consideration of counsels’ location.)

Judge Willett’s opinion also downplayed the role of docket congestion, which is too often “speculative,” and it limited the relevance of the “localized controversy” factor. Cases are localized if all the parties and the cause of action are based in one place. (I have made a similar argument based on the old admiralty cases from which FNC doctrine derives.) But some cases are “completely diffuse” because they involve matters of broader public interest. In such cases, the “localized controversy” and jury duty considerations are irrelevant.

In an earlier iteration of that same CFPB litigation, Judge Oldham wrote separately to criticize the district court for discounting the plaintiffs’ choice of forum just because some of the plaintiffs had sued far from home. This, to be clear, is precisely what Piper directed courts to do in the FNC context. But in the § 1404 context, Judge Oldham explained, “I am unaware of any support in our precedent or the Supreme Court’s for this less-respect rule. To the contrary, we have never put a geographic caveat on our repeated statements about the plaintiff’s choice of venue” needing to be respected. Further, he worried that the stakes of a § 1404 transfer are higher if the transfer would send the case out of the Fifth Circuit: “Query whether a higher burden should be met in advocating a § 1404(a) transfer from a district court in one circuit to a district court in another circuit more than 1,000 miles away.”

Leveling Up?

To be clear, I agree with a lot of this reasoning! Plaintiffs’ choice of forum should generally be respected, and trumped-up arguments about the plaintiffs’ convenience or the vague difficulties of gathering evidence from outside the district should be discounted. But it is concerning that these reforms are coming fast and furious (the above is just a partial selection)—and in cases with a particular ideological tilt.

One way that the Fifth Circuit could reassure court observers that these decisions are not purely results-oriented would be to extend these insights to FNC. If transferring a case from one federal district to another more than 1,000 miles away merits extra scrutiny, shouldn’t the dismissal of a case with a direction to refile it in a foreign court more than twice that far merit even more?