Throwback Thursday: Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino

March 21, 2024

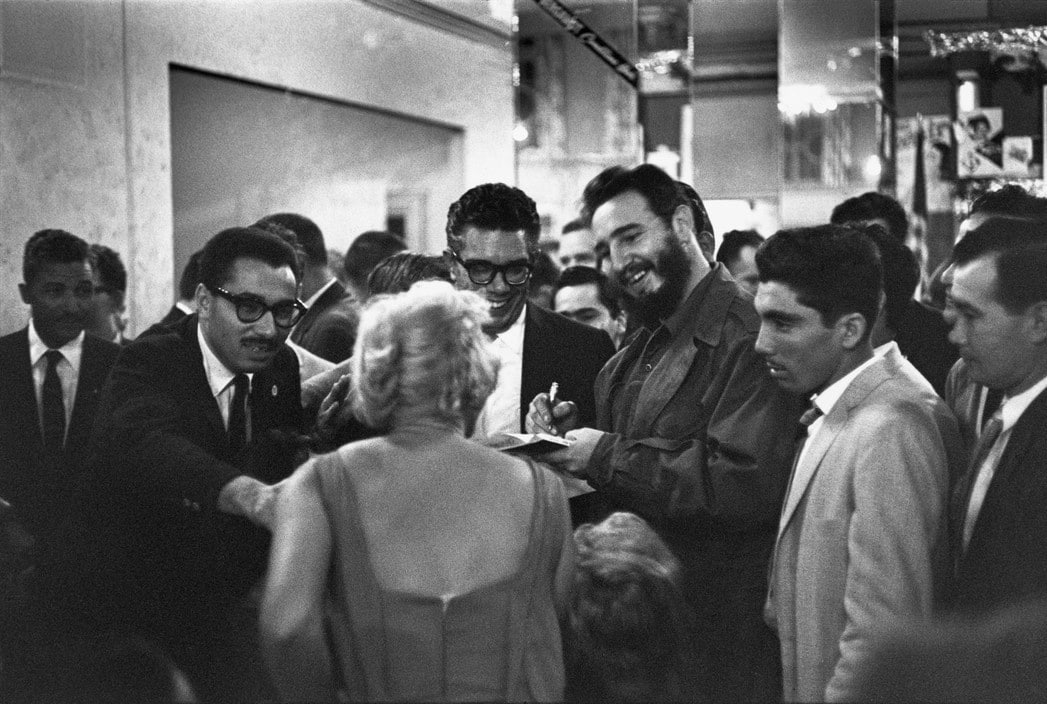

“Fidel Castro, EE.UU. Nueva York.

Distrito de Harlem. Hotel Theresa. 1960.”

is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Sixty years ago, on March 23, 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino. By a vote of 8-1, the Court held that the act of state doctrine prevented U.S. courts from questioning the validity of Cuba’s expropriations of property owned by U.S. nationals, even if the takings allegedly violated customary international law.

What initially seemed like a defeat for the application of customary international law in U.S. courts has subsequently been interpreted as support for the claim that customary international law is federal common law. At the same time, the Supreme Court’s narrowing of the act of state doctrine in W.S. Kirkpatrick & Co. v. Environmental Tectonics Corp. (1990) has undermined the justification for the doctrine itself as a rule of federal common law. In this Throwback Thursday post, I look back at the Sabbatino case and discuss some of what has happened since.

Who Owned the Sugar?

On August 6, 1960, Cuba nationalized a number of U.S.-owned companies, including Compania Azucarera Vertientes-Camaguey de Cuba (CAV), a Cuban company principally owned by U.S. nationals. An American commodity broker, Farr, Whitlock & Co., had contracted to buy sugar from a subsidiary of CAV for delivery to Morocco. To obtain release of the sugar, which was sitting on board a ship in a Cuban port, Farr Whitlock executed a new contract with the Cuban government. Farr Whitlock owed someone for the sugar, but whom? The answer turned on whether Cuba’s expropriation was valid. If it was valid, Cuba owned the sugar and was entitled to payment. If it was not, CAV owned the sugar and was entitled to payment.

To enforce Cuba’s claim, Banco Nacional de Cuba sued Peter Sabbatino, a New York lawyer appointed temporary receiver of CAV’s New York assets who was holding the funds received from Farr Whitlock. Both the district court and the Second Circuit held that Cuba’s expropriation was invalid because it violated customary international law.

Justice Harlan’s Opinion

Writing for the Supreme Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan II held that the act of state doctrine barred U.S. courts from questioning the validity of an expropriation of property by a recognized foreign government within its own territory “even if the complaint alleges that the taking violates international law.”

The act of state doctrine was not “compelled either by the inherent nature of sovereign authority … or by some principle of international law,” Harlan wrote. Nor was it required by the Constitution. But it did “have ‘constitutional’ underpinnings.”

It arises out of the basic relationships between branches of government in a system of separation of powers. It concerns the competency of dissimilar institutions to make and implement particular kinds of decisions in the area of international relations. The doctrine as formulated in past decisions expresses the strong sense of the Judicial Branch that its engagement in the task of passing on the validity of foreign acts of state may hinder rather than further this country’s pursuit of goals both for itself and for the community of nations as a whole in the international sphere.

Courts, Harlan explained, are good at applying widely accepted rules to facts. The problem in this case was that communist countries and those emerging from colonialism had questioned the traditional U.S. position that expropriation was unlawful under customary international law if it was not for a public purpose, was discriminatory, or was not accompanied by prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. “There are few if any issues in international law today on which opinion seems to be so divided,” Harlan wrote, “as the limitations on a state’s power to expropriate the property of aliens.”

The executive branch was better positioned to provide redress. “Following an expropriation of any significance,” Harlan noted, “the Executive engages in diplomacy aimed to assure that United States citizens who are harmed are compensated fairly.” The executive could represent “all claimants of this country,” whereas the judiciary’s ability to address expropriations depended “on the fortuitous circumstance of the property in question being brought into this country.”

Harlan worried that for courts to question the validity of foreign acts of state “could seriously interfere with negotiations being carried on by the Executive Branch.” Even if the State Department declared that the expropriation violated customary international law, as it had here, a court decision so holding “might increase any affront.” “Considerably more serious and far-reaching consequences would flow from a judicial finding that international law standards had been met if that determination flew in the face of a State Department proclamation to the contrary.” In the shadow of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, avoiding interference with the executive’s conduct of foreign policy seemed wise.

Of course, as Justice White pointed out in a lone dissent, the Court’s statement that international opinion was divided on expropriation came close to saying that no such rules of international law existed. “I fail to see how greater embarrassment flows from saying that the foreign act does not violate clear and widely accepted principles of international law,” he wrote, “than from saying, as the Court does, that nonexamination and validation are required because there are no widely accepted principles to which to subject the foreign act.”

Although Justice Harlan tried to make clear that the Court’s decision “in no way intimates that the courts of this country are broadly foreclosed from considering questions of international law,” Sabbatino cast a “profound chill” on the willingness of U.S. courts to apply rules of customary international law.

Rising from the Ashes

One part of the Justice Harlan’s opinion would in time prove helpful to proponents of customary international law. In Part V, Harlan declared that the act of state doctrine was a rule of “federal common law” binding on state courts.

It seems fair to assume that the Court did not have rules like the act of state doctrine in mind when it decided Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins. Soon thereafter, Professor Philip C. Jessup, now a judge of the International Court of Justice, recognized the potential dangers were Erie extended to legal problems affecting international relations. He cautioned that rules of international law should not be left to divergent and perhaps parochial state interpretations. His basic rationale is equally applicable to the act of state doctrine.

In the article cited by the Court, Jessup had argued that Erie had “no direct application to international law.” “It would be as unsound as it would be unwise,” he wrote, “to make state courts our ultimate authority for pronouncing the rules of international law.”

To be clear, Sabbatino did not hold that customary international law was federal common law. It held that the act of state doctrine—a doctrine not required by international law—was federal common law. Still, it is hard to read the quoted passage as anything but an endorsement of Jessup’s position. The Restatement (Second) of Foreign Relations Law, published the following year, observed that Sabbatino’s holding that Erie does not apply to the act of state doctrine “would appear to apply a fortiori to questions of international law.” The Restatement (Third) was even more explicit: “Based on the implications of Sabbatino, the modern view is that customary international law in the United States is federal law and its determination by the federal courts is binding on State courts.”

After Sabbatino

Congress acted almost immediately to reverse the decision in Sabbatino, enacting the Second Hickenlooper Amendment, which directed U.S. courts to “giv[e] effect to the principles of international law” in cases of expropriation occurring after January 1, 1959. On remand, the district court applied this provision to Sabbatinoitself, so CAV’s owners were paid for the sugar in the end.

In 1976, Congress passed the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) and created an exception to foreign state immunity, based on the Second Hickenlooper Amendment, for cases “in which rights in property taken in violation of international law are in issue.” The exception has been used in many cases to seek recovery of artworks expropriated by the Nazis.

But compensation for the victims of Cuba’s expropriations has been long in coming. The U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission has adjudicated more than 8,800 claims and awarded more than $1.9 billion in damages. But because the United States has not reached a settlement with Cuba, there is no money to pay these claims.

In 1996, Congress passed the Helms-Burton Act, Title III of which allows U.S. victims to sue any person who “traffics” in expropriated property. Successive U.S. Presidents suspended this provision until 2019, when President Trump allowed the first suits to be filed. Although Congress’s findings make clear that Title III was enacted to discourage foreign companies from investing in Cuba by threatening them with liability, most of the suits have been brought against U.S. companies because of limits on personal jurisdiction.

The Act of State Doctrine Today

The Supreme Court’s 1990 decision in W.S. Kirkpatrick & Co. v. Environmental Tectonics Corp. significantly narrowed the act of state doctrine, limiting it to cases in which the validity of a foreign act of state as “a rule of decision” was at issue. The Court unanimously rejected the U.S. government’s suggestion that the doctrine should turn on the views of the executive branch regarding a case’s impact on foreign policy. “The act of state doctrine does not establish an exception for cases and controversies that may embarrass foreign governments,” Justice Scalia wrote for the Court, “but merely requires that, in the process of deciding, the acts of foreign sovereigns taken within their own jurisdictions shall be deemed valid.”

I have previously suggested that by narrowing the act of state doctrine, Kirkpatrick undermined the justification for its existence as a rule of federal common law. As the Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law explains (§ 441 comment a), the modern act of state doctrine “operates as a special choice-of-law rule in that it precludes a court from denying effect to an official act on the ground that the act violates the public policy of the forum.” But in the United States, choice of law is governed by state law, not federal law.

Recently, in Cassirer v. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation (2022), the Supreme Court declined to create federal choice of law rules for cases under the FSIA, seeing “scant justification for federal common lawmaking in this context.” If there is scant justification federal choice of law rules in suits against foreign states, what justification is there for such rules in suits that question the validity of their acts?